16 FROM PUBLIC GOOD TO PERSONAL PURSUIT: HISTORICAL ROOTS OF THE STUDENT DEBT CRISIS

FROM PUBLIC GOOD TO PERSONAL PURSUIT: HISTORICAL ROOTS OF THE STUDENT DEBT CRISIS

Preview the Article

Follow the steps below to preview the article “From Public Good to Personal Pursuit: Historical Roots of the Student Debt Crisis.” Ideally, you should print the article and write your responses in the margins of the printed copy. To read more about previewing, visit the chapter on previewing a reading.

- Read the title. What does it make you think about? What do you think the article is about? What questions do you have? Record your predictions and questions on the printed copy of the article next to the title.

- What do you know about student debt, and what concerns, if any, do you have about student debt?

- Read the first three paragraphs. What additional predictions do you now have about the article? What additional questions do you have? Record them on the printed copy of the article.

- Scan the article and notice the headings (e.g. Cost of a college degree today) within the article. What additional thoughts or questions do these raise? Record them on the printed copy of the article.

- Scan the bolded and underlined vocabularyin the article. If there are any words that you do not know well, look them up in a print or online dictionary and write some notes about their meanings on the printed copy of the article. Keep in mind that some words have multiple meanings. For example, the word shoulder is used in paragraph 6 in the article; however, it is not the noun that refers to a body part. It is a verb in the article. You may need to read the sentence containing the word to understand the word’s usage.

- Based on your preview of the article, what do you think is the central point of the article? (Don’t worry if you are not sure. This is a prediction or guess – you do not have to be correct as long as you are engaging your brain.) Record your prediction on the printed copy of the article.

- Based on your preview, do you predict that the article is narrative, expository, or argumentative?

Read Interactively

Now, read the article using the guidelines from the chapter on reading interactively. As you read, follow these steps to engage with the text.

- Pause to confirm or revise your predictionsand to answer the questions you posed while previewing the article. Write down those revised predictions and responses to the questions as you read. If you cannot find the answers to your questions, save them for further research and discussion.

- Pause at other points to check for understandingof what you just read. Can you explain key ideas in your own words yet? If not, reread to clarify. Ideas that come later in a text build on the previous ones. Therefore, it makes no sense to keep reading if you did not understand something or if you became distracted. Anyone can become distracted while reading, so don’t hesitate to use the strategy of rereading when necessary.

- Pay attention to any vocabularywords that are confusing. Look up the words in a dictionary if they are interfering with your understanding, or mark them to return to later.

- Record any opinions or reactionsyou have to the reading in the margins of the article.

- Write down any further questionsthat develop as you read.

From public good to personal pursuit: Historical roots of the student debt crisis

Thomas Adam, University of Texas Arlington

June 29, 2017

1 The promise of free college education helped propel Bernie Sanders’ 2016 bid for the Democratic nomination to national prominence. It reverberated during the confirmation hearings for Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education and Sanders continues to push the issue.

2 In conversations among politicians, college administrators, educators, parents and students, college affordability seems to be seen as a purely financial issue – it’s all about money.

3 My research into the historical cost of college shows that the roots of the current student debt crisis are neither economic nor financial in origin, but predominantly social. Tuition fees and student loans became an essential part of the equation only as Americans came to believe in an entirely different purpose for higher education.

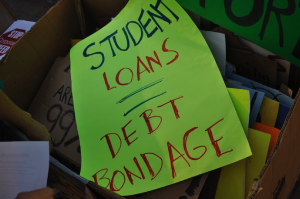

Students took to the streets to protest their debt burdens as part of Occupy Boston in 2011. CampusGrotto/flickr, CC BY-NC

Cost of a college degree today

4 For many students, graduation means debt. In 2012, more than 44 million Americans (14 percent of the total population) were still paying off student loans. And the average graduate in 2016 left college with more than $37,000 in student loan debt.

5 Student loan debt has become the second-largest type of personal debt among Americans. Besides leading to depression and anxiety, student loan debt slows down economic growth: It prevents young Americans from buying houses and cars and starting a family. Economist Alvaro Mezza, among others, has shown that there is a negative correlation between increasing student loan debt and homeownership.

6 The increase in student loan debt should come as no surprise given the increasing cost of college and the share that students are asked to shoulder. Decreasing state support for colleges over the last two decades caused colleges to raise tuition fees significantly. From 1995 to 2015, tuition and fees at 310 national universities ranked by U.S. News rose considerably, increasing by nearly 180 percent at private schools and over 225 percent at public schools.

7 Whatever the reason, tuition has gone up. And students are paying that higher tuition with student loans. These loans can influence students’ decisions about which majors to pick and whether to pursue graduate studies. (See data on US Student Debt vs. College Tuition.)

Early higher education: a public good

8 During the 19th century, college education in the United States was offered largely for free. Colleges trained students from middle-class backgrounds as high school teachers, ministers and community leaders who, after graduation, were to serve public needs.

9 This free tuition model had to do with perceptions about the role of higher education: College education was considered a public good. Students who received such an education would put it to use in the betterment of society. Everyone benefited when people chose to go to college. And because it was considered a public good, society was willing to pay for it – either by offering college education free of charge or by providing tuition scholarships to individual students.

10 Stanford University, which was founded on the premise of offering college education free of charge to California residents, was an example of the former. Stanford did not charge tuition for almost three decades from its opening in 1891 until 1920.

11 Other colleges, such as the College of William and Mary, offered comprehensive tuition scholarship programs, which covered tuition in exchange for a pledge of the student to engage in some kind of service after graduation. Beginning in 1888, William and Mary provided full tuition scholarships to about one third of its students. In exchange, students receiving this scholarship pledged to teach for two years at a Virginia public school.

12 And even though the cost for educating students rose significantly in the second half of the 19th century, college administrators such as Harvard President Charles W. Eliot insisted that these costs should not be passed on to students. In a letter to Charles Francis Adams dated June 9, 1904, Eliot wrote, “I want to have the College open equally to men with much money, little money, or no money, provided they all have brains.” (See data on College Tuition in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries.)

College education becomes a private pursuit

13 The perception of higher education changed dramatically around 1910. Private colleges began to attract more students from upper-class families – students who went to college for the social experience and not necessarily for learning.

14 This social and cultural change led to a fundamental shift in the defined purpose of a college education. What was once a public good designed to advance the welfare of society was becoming a private pursuit for self-aggrandizement. Young people entering college were no longer seen as doing so for the betterment of society, but rather as pursuing personal goals: in particular, enjoying the social setting of private colleges and obtaining a respected professional position upon graduation.

15 In 1927, John D. Rockefeller began campaigning for charging students the full cost it took to educate them. Further, he suggested that students could shoulder such costs through student loans. Rockefeller and like-minded donors (in particular, William E. Harmon, the wealthy real estate magnate) were quite successful in their campaign. They convinced donors, educators and college administrators that students should pay for their own education because going to college was considered a deeply personal affair. Tuition – and student loans – thus became commonly accepted aspects of the economics of higher education.

16 The shift in attitude regarding college has also become commonly accepted. Altruistic notions about the advancement of society have generally been pushed aside in favor of the image of college as a vehicle for individual enrichment.

A new social contract

17 If the United States is looking for alternatives to what some would call a failing funding model for college affordability, the solution may lie in looking further back than the current system, which has been in place since the 1930s.

18 In the 19th century, communities and the state would foot the bill for college tuition because students were contributing to society. They served the common good by teaching high school for a certain number of years or by taking leadership positions within local communities. A few marginal programs with similar missions (ROTC and Teach for America) still exist today, but students participating in these programs are very much in the minority.

19 Instead, higher education today seems to be about what college can do for you. It’s not about what college students can do for society.

20 I believe that tuition-free education can only be realized if college education is again reframed as a public good. For this, students, communities, donors and politicians would have to enter into a new social contract that exchanges tuition-free education for public services.

Students from UC Davis working on a environmental restoration project in 2013. Could a tuition-free, service-oriented approach be the future of higher education? Jonathan Su/flickr, CC BY-SA

Thomas Adam, Professor of Transnational History, University of Texas Arlington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Reflect

After reading the article, use the following questions to reflect on the content of the article and your reading process. See the chapter about reflecting for a discussion of why this is a crucial step.

- Try to paraphrase the main idea in a sentence. This may be challenging because you have read the article only once. If you are struggling, do your best. You can refine this when you reread and summarize the article.

- Is the article primarily narrative, expository, or argumentative? What is the purpose of the article? In other words, why do you think the author wrote it?

- Which predictions were accurate, and which did you have to revise?

- As you previewed the article, you wrote questions. What questions remain unanswered after reading the article?

- What else do you want to know about the article or topic of the reading? Write down any additional questions.

- How did previewing the article help you to understand and engage with the text while reading?

- Where did you struggle to understand something in the text, and how did you work through it?

- What, if anything, could you have done differently to improve your reading process?

Summarize

Complete a summary of the article by following these steps. Make sure you have read the chapters about Reading to Summarize before proceeding with the summary.

- Reread the article and complete the Summary Notes. See Preparing to Summarizefor a review of this topic and an example.

- Then, use your Summary Notes to write a one-paragraph summary of the article. See Writing a Summaryfor a review of this topic and an example. Make sure that you include in-text citations and the Work Cited.

- Use the self-assessment/peer review questions from Evaluating a Summaryto self-assess your summary or invite a peer to provide feedback.

- Use the self-assessment or peer feedback to make changes to your summary.