6 The Social Determinants of Health

What are the Social Determinants of Health?

To understand how racism contributes to health, it is first necessary to examine the Social Determinants of Health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) as the nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes. These are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, as well as the broader set of forces and systems that shape daily life. Such forces and systems include economic policies, development agendas, social norms, social policies, racism, climate change, and political structures.[1]

SDoH have significant impacts on the health, well-being, and quality of life of individuals.

-

Examples of SDoH

- Safe housing, transportation, and neighborhoods

- Racism, discrimination, and violence

- Education, job opportunities, and income

- Access to nutritious foods and physical activity opportunities

- Polluted air and water

- Language and literacy skills

The SDoH also contribute to significant health disparities and inequities. For example, people who lack access to grocery stores with healthy food options are less likely to maintain good nutrition. This limited access increases their risk of conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, and it can even reduce life expectancy compared with those who do have access to healthy foods.[2]

The Social Determinants of Health play a critical role in shaping individual health status and are closely correlated with health outcomes. People with higher socioeconomic status and greater access to education consistently experience better health, while those living in poverty or with limited education face poorer health outcomes. Poverty is associated with:

- Increased risk for chronic disease (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension)

- Shorter life expectancy

- Higher infant mortality rates

- Higher mortality rates

Poverty is a barrier to proper health care because it limits access to nutritious food and quality medical services. These limitations contribute to unhealthy behaviors and medical decisions that, in turn, lower life expectancy.

“Men in the bottom 1% of the income distribution at the age of 40 years had an expected age of death of 72.7 years. Men in the top 1% of the income distribution had an expected age of death of 87.3 years, which is 14.6 years (95% CI, 14.4-14.8 years) longer than those in the bottom 1%. Women in the bottom 1% of the income distribution at the age of 40 years had an expected age of death of 78.8 years. Women in the top 1% had an expected age of death of 88.9 years, which is 10.1 years (95% CI, 9.9-10.3 years) longer than those in the bottom 1%.”[3]

The above video is a summary of the JAMA article entitled: The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001 – 2014

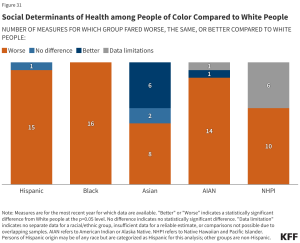

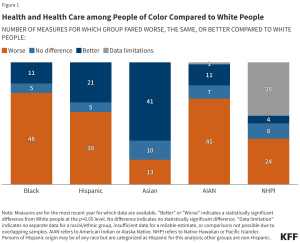

A 2024 analysis examining how people of color fared compared to White people across various health measures yielded considerable insight.[4]

The analysis revealed the following:

- Black, Hispanic, and AIAN (American Indian or Alaska Native) people fare worse than White people across the majority of examined measures of health and health care and social determinants of health

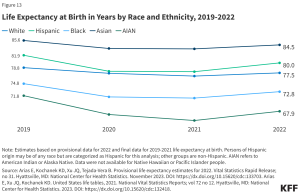

- AIAN (67.9 years) and Black (72.8 years) people had a shorter life expectancy compared to White people (77.5 years) as of 2022, and AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people experienced larger declines in life expectancy than White people between 2019 and 2022. The decrease in life expectancy for Black people is due to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color.

- Black (10.9 per 1,000) and AIAN (9.1 per 1,000) infants were at least two times as likely to die as White infants (4.5 per 1,000) as of 2022. Black and AIAN women also had the highest rates of pregnancy-related mortality.

- Black people remain more likely to be uninsured compared to their White counterparts.

Above data from: Ndugga, Nambi, et al. “Key Data on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity.” KFF, 21 May 2024, www.kff.org/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/?entry=executive-summary-introduction. Accessed, 14 September 2024.

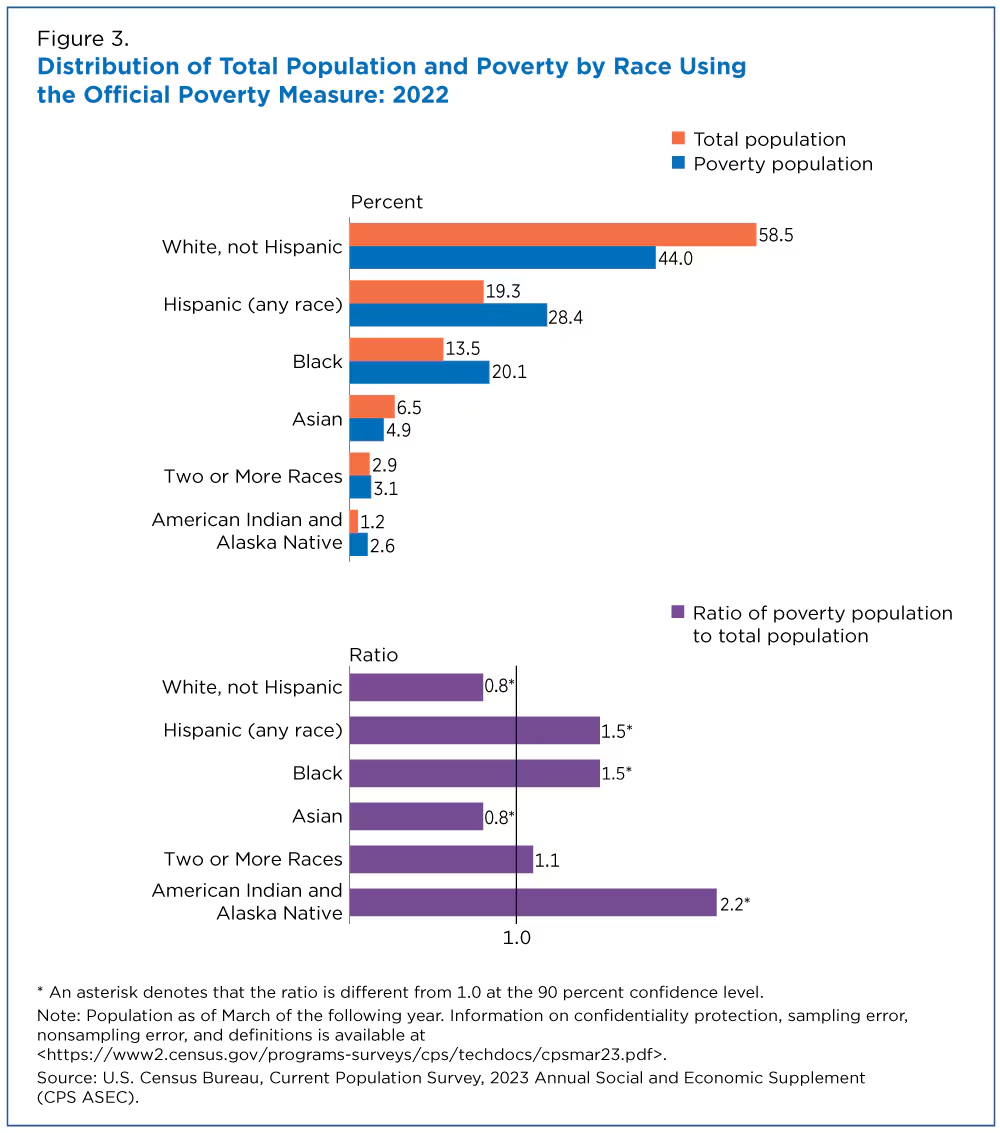

U.S. Census data reports that Black individuals experienced “record low” poverty rates in 2022. While this may be cause for celebration, the “record low” still falls well below parity with White Americans. According to the Census, in 2022 Black individuals made up 20.1% of the population in poverty but only 13.5% of the total population. This results in a ratio of 1.5, meaning that the Black population was overrepresented in poverty. Hispanic individuals (of all races) were represented at a similar level to Black individuals. However, with a ratio of 2.2, American Indians and Alaska Natives were the most overrepresented group in poverty in 2022. By contrast, White Americans had a ratio of 0.8.[5]

These data reflect staggering poverty rates that correlate with higher risk for chronic diseases, decreased life expectancy, and higher mortality rates, all of which have been shaped by historic racist acts of oppression against Black Americans.

Health and Racism in Black America

The above video discusses the concept of “weathering.” Weathering is discussed in detail in Part 3.

Although poor social determinants of health (SDoH) contribute significantly to health disparities among people of color, racism and discrimination are also key drivers of adverse health conditions and disparities in these populations. The health of Black Americans suffers irrespective of educational or socioeconomic status.

In his article Before Their Time, Ron Howell speaks about the devastating losses experienced by his Yale graduating class of 1970. The article highlights his concerns about an alarming fact: 41 years after graduating from Yale, the Black male members of the Yale class of 1970 had a death rate three times higher than that of the average class member.

“I think there may be 24 (or more) such men, none of whom got past age 62, most not even seeing their 60th year. It is astonishing and disturbing.”

~ Charles S. Finch III, Yale Class of 1970

“It struck me recently that we of the Class of ’70 were barely a century out of America’s slavery era when we entered Yale, and the civil rights era was barely beginning to bloom. I am a writer, not a doctor. But I believe that racially based stress, of the kind many black men suffered and still suffer, is akin to a hypertension that becomes fixed in one’s system over time, leading to death if it isn’t treated.”

~ Ron Howell, Yale Class of 1970

- https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html ↵

- https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health ↵

- Chetty RStepner MAbraham S, et al. The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4226 ↵

- Key Data on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity ↵

- Shrider E. Poverty Rare for the Black Population Fell Below Pre-Pandemic Levels. Census. 2023. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ ↵