11 The Heckler Report

“Racism is not a big deal in America. Black people only make it a big deal because they are still upset about slavery, but that was in 1860 and slavery helped America. People should get over it so we can move on.”

— Salina, Kansas High School Student –Reference: N.A. Student’s article on ‘modern racism’ sparks controversy in Salina. KWCH 12.[1]

In 1944, economist and Nobel Prize winner Gunnar Myrdal, in his classic study of the role of race in American life, observed that “area for area, class for class, Negroes cannot get the same advantages in the way of prevention and care of disease that Whites can.” –Myrdal, Gunnar. “An American dilemma; the Negro problem and modern democracy.(2 vols.).” (1944).

Despite longstanding knowledge that health disparities disproportionately affect Black Americans in the United States, the first government-sanctioned study examining the impact of these disparities on the health of minorities was not conducted until 40 years later. This landmark study became known as The Heckler Report[2]

In 1985, Margaret Heckler, Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, published the landmark Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. Also known as the Heckler Report, it presented the results of a U.S. government-sponsored investigation into racial and ethnic health disparities. This was the first time the federal government undertook a comprehensive examination of the health status of racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. The report brought national attention to minority health by highlighting significant and indisputable disparities affecting these populations.

The report stated: “Despite the unprecedented explosion of scientific knowledge and the phenomenal capacity of medicine to diagnose, treat, and cure disease, Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and those of Asian/Pacific Islander heritage have not benefited fully or equitably from the fruits of science or from systems responsible for translating and using health sciences technology.”

The study underscored the need for immediate and sustainable interventions to improve the health of minorities, noting that health disparities accounted for 60,000 excess deaths per year in the United States. Analyzing mortality data from 1979 to 1981, the task force identified six causes of death that accounted for more than 80 percent of the deaths observed among Black and other minority groups compared to the White population.

*An excess death is the difference between the observed deaths in specific periods and the expected deaths in the same time periods.

Causes of Excess Death Among Blacks and Other Minorities According the to 1985 Heckler Report

- Cancer

- Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke

- Chemical Dependency, measured by deaths due to cirrhosis

- Diabetes

- Homicide, suicide, and accidents

- Infant mortality and low birth weight

The Heckler Report concluded that although health was improving significantly for Americans overall, Black and other minority populations in the United States continued to experience disparities that led to excess premature deaths. The report recommended targeted and culturally responsive interventions, including education

and outreach campaigns that emphasized health literacy and preventive care, to increase health equity and reduce disparities among Black and other minority groups. The task force also highlighted the need to remove barriers, expand access to healthcare, and actively collect data related to minority health in order to better address these inequities. To coordinate the implementation of the task force’s recommendations, Secretary Heckler established the Office of Minority Affairs within the Department of Health and Human Services.

Despite Myrdal’s 1944 study, the evidence presented in the Heckler Report, and subsequent efforts to eliminate disparities, the United States still grapples with health inequities that continue to negatively impact people of color nearly 80 years later.

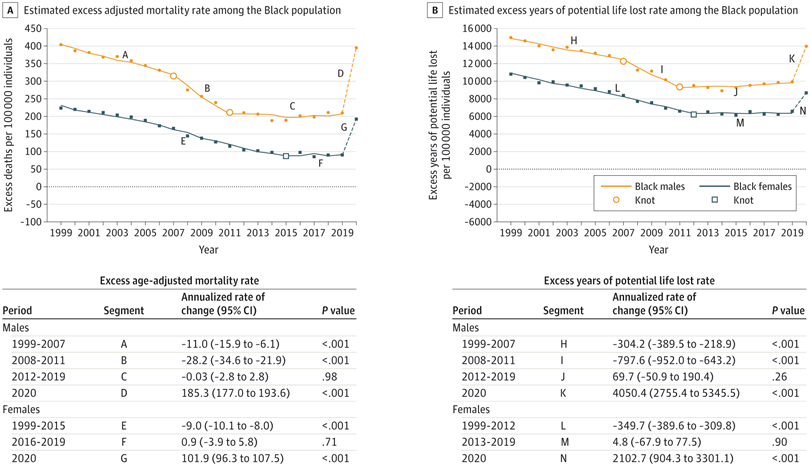

Excess Mortality and Years of Potential Life Lost Among the Black Population in the US, 1999-2020

In May 2023, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a cross-sectional study that analyzed U.S. national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1999 through 2020.[3] The results of the study revealed that:

“Over a recent 22-year period, the Black population in the US experienced more than 1.63 million excess deaths and more than 80 million excess years of life lost when compared with the White population.”

The study co-author and Yale professor, Harlan Krumholz said: “Our efforts to address health equity have failed to produce sustainable improvements”. While, another co-author, also a professor at Yale, Marcella Nunez-Smith, said, “This is not an abstract concept. There is a real human toll to these entrenched inequities. The impact on families and communities should be unacceptable to all of us.” The study authors assert that “race offers no intrinsic biological reason for those categorized as Black individuals to have worse outcomes than White individuals, indicating therefore that these disparities are driven by the burden of acquired risk factors, the influence of social determinants of health, limitations in access to care, and structural barriers indicative of bias (ie, structural racism).”

- https://www.kwch.com/content/news/Students-article-on-modern-racism-sparks-controversy-in-Salina-448071783.html ↵

- https://archive.org/details/reportofsecretar00usde/page/n10/mode/1up ↵

- Caraballo C, Massey DS, Ndumele CD, et al. Excess Mortality and Years of Potential Life Lost Among the Black Population in the US, 1999-2020. JAMA. 2023;329(19):1662–1670. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.7022 ↵