9 Racism in the Literature

Racism is a key driver of health disparities across racial and ethnic groups. We have discussed how cultural incompetence and racial bias disadvantage patients of color during medical encounters. Combined with systems of oppression that lead to poverty, unsafe housing, and limited educational opportunities, these factors amplify the risk of multiple health disparities. Literature that addresses racism and its impacts helps raise awareness among healthcare providers, reduces bias, and can help instigate real change. For this reason, medical literature must directly examine the connection between health disparities and racism for health equity to be achieved. However, this is often not the case. Despite extensive data linking racism to poor health outcomes, many biomedical journals continue to fail to publish research on the subject.

“Ignorance is neither neutral nor benign, especially when it cloaks evidence of harm. And when ignorance is produced by gatekeeper medical institutions, as has been the case with obfuscation of at least 200 years of knowledge about racism and health, the damage is compounded. The racialized inequities exposed this past year—involving COVID-19, police brutality, environmental injustice, attacks on democratic governance, and more—have sparked mainstream awareness of structural racism and heightened scrutiny of the roles of scientific institutions in perpetuating ignorance about how racism harms health.” –Excerpted from Medicine’s Privileged Gatekeepers: Producing Harmful Ignorance About Racism and Health

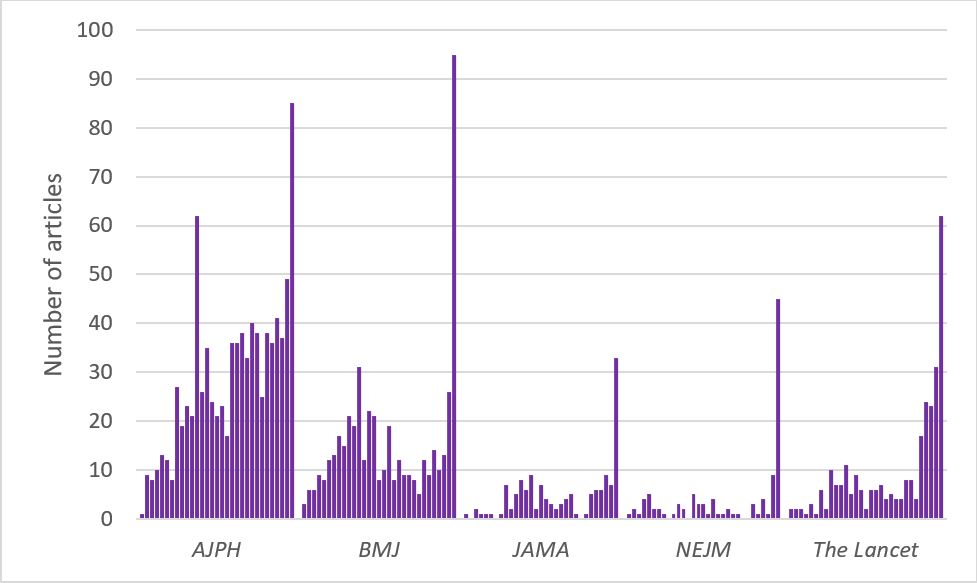

The article Medicine’s Privileged Gatekeepers: Producing Harmful Ignorance About Racism and Health examinded the use of the word “racism” in papers published between January 1, 1990 – and December 31, 2021, by the four leading medical journals.

- New England Journal of Medicine

- The Lancet

- JAMA

- British Medical Journal

The authors intentionally focused on the term “racism” because “naming racism is a critical step in addressing its impacts.” Mentions of the term in articles remained low until 2020, when there was a drastic increase. Nearly 90 percent of these articles were commentaries, viewpoints, or letters, and only 4 percent were based on primary investigations with significant data. In many cases, the term “racism” appeared only in the discussion section as a way to interpret study results. The authors argue that this trend does not reflect a lack of publishable research, but rather the failure of leading medical journals to publish primary studies linking racism to health. They cite four adverse consequences of this practice:

- It conveys the message that racism and its health implications are not important and do not warrant scientific study or publication.

- It fosters ignorance about these issues among healthcare professionals who are trusted sources of information, who then transmit this ignorance to their patients, clients, and the public.

- It prevents policymakers from grasping the full impact of racism, limiting the evidence needed to advocate for policies to prevent racism and its health implications.

- It excludes the work of scholars who study racism and health, effectively limiting public knowledge of the implications of racism’s impact on health, and also limiting the career trajectory of these scholars who “fail to publish.”

Despite overwhelming evidence of the connection between racism and health disparities, many journals fail to publish articles that establish this correlation. Without a substantial body of literature, the link between racism and health outcomes may be underrecognized or misunderstood by policymakers, healthcare providers, and the public.

A scoping review that included studies of any design (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method, meaning studies that use both qualitative and quantitative approaches) examined racism in healthcare and found that the earliest paper on the topic was published in 2001. Quantitative studies included in the review revealed that “reports of racism in healthcare that include both majority and racialized minorities (mostly African Americans) show that racialized minorities are more likely to report experiences of perceived racism and inadequate healthcare compared to majority groups in various contexts, such as in the USA.” Racialized minorities were subjected to both covert and overt racism from healthcare staff, with African American women reporting instances of racial slurs. Qualitative studies show that African Americans’ perceived experiences of racism include:

- Avoidance of touch by healthcare staff

- Exclusion from decision-making processes during healthcare interactions

- Lack of respect

- Being scolded, treated rudely, and with apathy by healthcare staff

Hispanic and Latina women reported similar perceived experiences of racism. These experiences often lead to avoidance of medical care, which further exacerbates health disparities. The articles reviewed examined the beliefs and perceptions of healthcare staff regarding minorities but did not explicitly investigate the role racism plays. Ultimately, the authors state:

Hispanics and Latinas reported similar perceived experiences of racism. These experiences result in an avoidance of medical care which further exacerbates health disparities. The included articles examined the beliefs and perceptions of healthcare staff regarding minorities but did not set out to look at the role racism plays. Ultimately, the authors state that:

“Research on racism in healthcare is fragmented and scattered across disciplines and healthcare contexts…Research on racism in healthcare shows that racism operates in various dimensions between healthcare staff and users and affects treatment and diagnosis in various health indicators…Research tends to ignore racialization processes in healthcare making it difficult to conceptualize racism in healthcare and understand how racism is produced in healthcare. Research on racism in healthcare could benefit from sociological research on racism and racialization to explain how overt racism is produced and how racism is normalized and hidden behind supposedly non-racial practices in healthcare.”

Based on their review, the authors submit the following key recommendations on future research on racism:

- Research should attempt to understand the various processes through which racism is (re)produced in healthcare.

- Research should apply clear definitions of racism and should not use racial categories uncritically as this may risk (re)producing racializing discourse in healthcare research.

- Research could benefit from sociological theorizing to conceptualize racism and processes of racialization in healthcare.

- Research should attempt to examine how denial of racism in healthcare may contribute to the reproduction of racism.

- Research should extend to other contexts outside of the USA to capture other perspectives of racism.

Reference: Hamed, S., Bradby, H., Ahlberg, B. M., & Thapar-Björkert, S. (2022). Racism in healthcare: a scoping review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 988.

Calling out racism in the medical literature is critical if health equity is the goal, as doing so directly impacts those who experience health disparities. As discussed, racism significantly affects health outcomes by contributing to disparities in access to healthcare, quality of treatment, and overall health. Better and more consistent documentation of how racism influences health can improve outcomes by shaping medical education and helping providers deliver more culturally competent care. This, in turn, can foster increased trust and stronger patient-provider relationships. In addition, greater publication of research that directly examines the connection between racism and health disparities can build awareness of its impact, better inform medical education, enhance training, and encourage evidence-based strategies to reduce health disparities. More importantly, increased publications on racism’s impact on health will provoke discussions that can drive systemic change in healthcare by influencing policies and practices, bridging the racism-driven gap in access to quality care for communities of color, and fostering a more equitable healthcare system.