13 Race as a Biological Concept

Race-based medicine attributes biological differences to racial groups and uses these assumptions to guide medical practice and treatment decisions. These practices impute bias into a system that results in subpar care for blacks and can have life and death consequences. Despite the finding that the human genome lacks any genetic basis for race, race is embedded in every facet of medicine, from assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Clinicians use race-based corrections to help determine medication and dosages, which patients have access to specialists, organ transplants, clinical trials, and even insurance coverage. However, the rationale for using them is unclear, and more importantly, it is unclear which of these corrections mitigate health disparities and which ones do further harm to people of color.

Evidence justifying these corrections is stark, and while historians have searched for the answers, much of it is missing, confounded with other variables, or resulting from racist stereotypes birthed by scientific racism. The assertion of biological differences between races, and the invention of “illnesses” similar to those “discovered” by white supremacists, were accepted into medical education and practice, where they continue to perpetuate racist tropes. These practices are outdated and are scientifically unsupported.

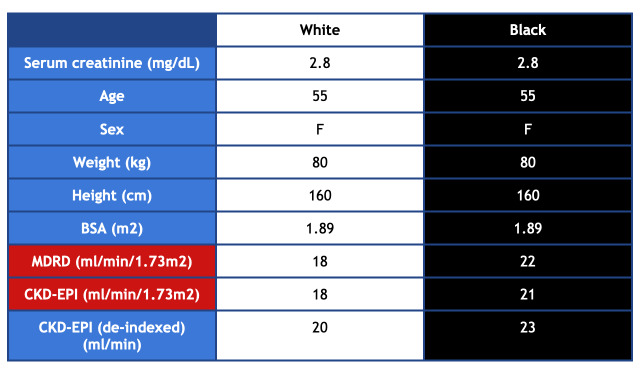

Below are examples of how race is used as a proxy in medical decision-making.

The examples above are only a few instances of race-based corrections used in medicine today, but there are many others. In her publication Hidden in Plain Sight: Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms[1], author Darshali Vyas asserts that race corrections operate on the assumption that genetic differences correlate with race, despite decades of evidence showing greater genetic variation among individuals within the same race than between races. These corrections also fail to account for the challenges posed by individuals of mixed race. If race is intrinsic to biology, how do we “correct” for this context? And if a provider is tasked with determining a patient’s race, how can accuracy be ensured in assigning that race? These are fundamental questions that must be addressed if eliminating health disparities and achieving health equity are the ultimate goals.

Examples of Race-Based Correction in Clinical Medicine

- Vyas, Darshali A., Leo G. Eisenstein, and David S. Jones. "Hidden in plain sight—reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms." New England Journal of Medicine 383.9 (2020): 874-882. ↵