14 COVID-19: The Perfect Storm

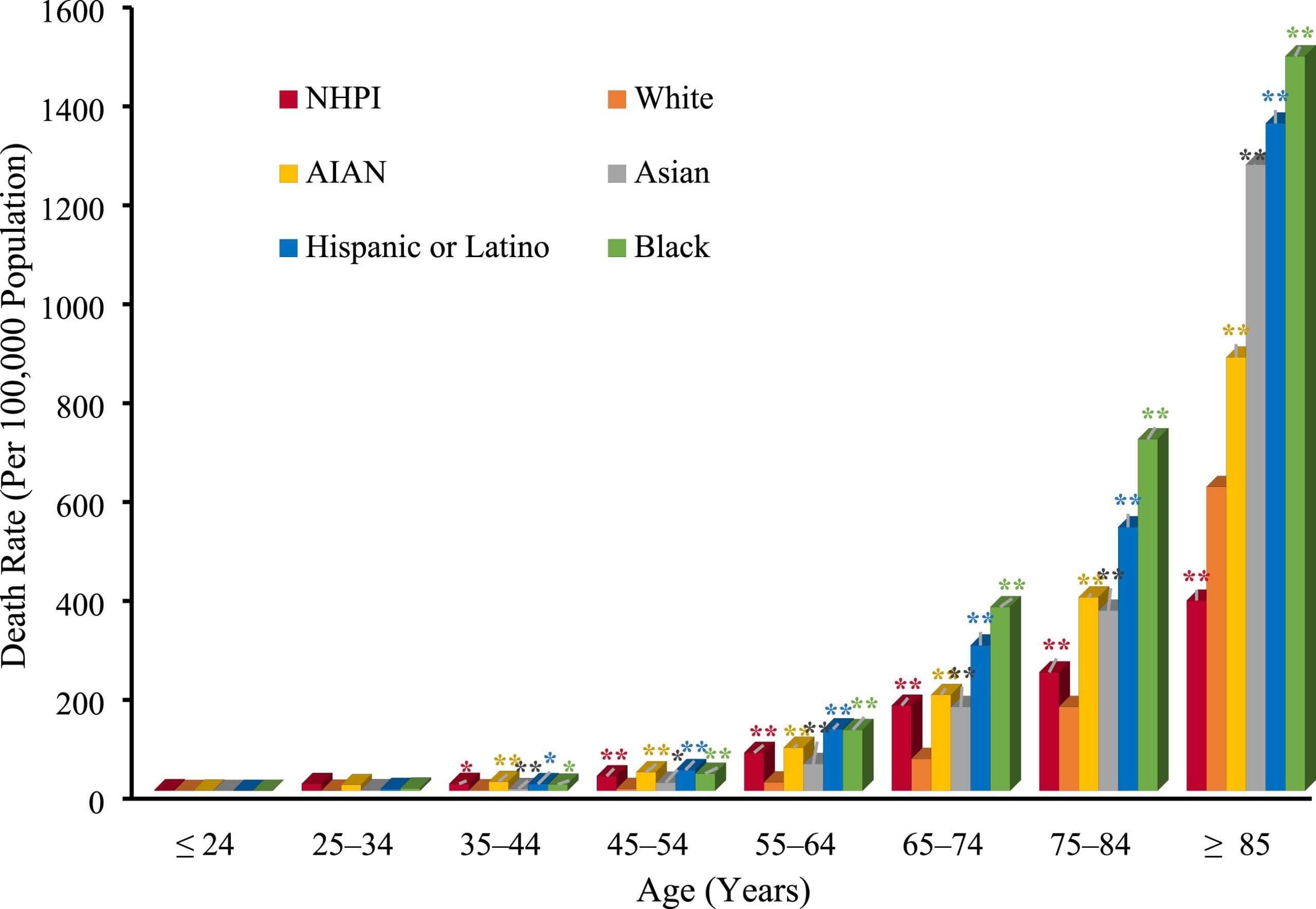

COVID-19 has illuminated how racial inequities across multiple institutions in the United States have converged to produce profound and lasting negative impacts on people and communities of color. These inequities created the perfect storm, allowing COVID-19 to take full advantage and devastate these communities. Disparities in the treatment of people of color, combined with preexisting health disparities more prevalent in these populations, have resulted in COVID-19 death rates up to 3.5 times higher than those of White counterparts and significantly higher than their share of the population. These deaths have not only meant the loss of physical presence but have also perpetuated the cycles that contribute to discrimination and other social injustices.

As discussed previously, minority status is often correlated with low socioeconomic status and conditions of poverty. The consequences of poverty are associated with numerous factors that increase the risk of exposure to COVID-19.

These include:

- Residing in dwellings that may be crowded and/or multigenerational

- Essential worker status that prevents remote work

- Bus drivers

- Grocery store/food industry work

- Nurses

- Essential tradesmen (plumbers, electricians, construction workers)

- Need for public transport

Lower socioeconomic status is also correlated with higher rates of chronic diseases that increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 infection and death. These include:

- Asthma

- Hypertension

- Obesity

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Diabetes

- Chronic respiratory disease

Although disparities in infection and death have decreased throughout the pandemic, early analyses of racial trends revealed that infection and death rates in predominantly Black counties were three and six times higher, respectively, than those in predominantly White counties. For example, in Milwaukee County, home to Wisconsin’s largest city, Black residents made up only 26 percent of the population but accounted for 70 percent of COVID-19 deaths. Similar patterns were observed statewide in Louisiana, where in April 2020, Black residents accounted for 72 percent of deaths while making up only 32 percent of the state’s population. In many of these deaths, hypertension was the leading underlying cause.

References

- Thebault, R., Williams, V. and Tran, A. (2020) African Americans are at higher risk of death from coronavirus – The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows/ (Accessed: 04 October 2024).

- Racial disparities in Louisiana’s COVID-19 death rate reflect systemic problems. 4WWL. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed April 3, 2024. Available at: https://www.wwltv.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/racial-disparities-in-louisianas-covid-19-death-rate-reflect-systemic-problems/289-bd36c4b1-1bdf-4d07-baad-6c3d207172f2

Equitable Data Collection and Disclosure on COVID-19 Act of 2020

Despite prior knowledge of how minority communities had fared during past epidemics, stark data quickly emerged to assess the impact of COVID-19 on these communities in the early days of the pandemic. What became clear from the available information were the staggering rates of infection and death among minorities across the United States. The lack of transparency in these data led to public calls for the collection and release of COVID-19 statistics disaggregated by race.

On April 14, 2020, Congresswomen Ayanna Pressley, Karen Bass, Chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, Robin Kelly, Chair of the Congressional Black Caucus Health Braintrust, and Barbara Lee, along with Senators Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Edward J. Markey, Jeff Merkley, and more than 85 of their colleagues, introduced the Equitable Data Collection and Disclosure on COVID-19 Act. The bill required the Department of Health and Human Services to collect and report racial, ethnic, and other demographic data on COVID-19 testing, treatment, and fatality rates, and to provide both a summary of the final statistics and a report to Congress within 60 days after the end of the public health emergency.

“Specifically, the bill would require HHS to use all available surveillance systems to post daily updates on the CDC website showing the following data disaggregated by race, ethnicity, sex, age, socioeconomic status, disability status, county, and other demographic information, including:

- Data related to COVID-19 testing, including the number of individuals tested and the number of tests that were positive;

- Data related to treatment for COVID-19, including hospitalizations and intensive care unit admissions and duration; and

- Data related to COVID-19 outcomes, including fatalities.

The bill also would establish an inter-agency commission to make recommendations in real time on improving data collection and transparency and responding equitably to this crisis.”[1]

Click here to read the full text of the Equitable Data Collection and Disclosure on COVID-19 Act

Soon after this statement was made public, states began releasing COVID-19 data by race and ethnicity. However, by July 2020, 56 percent of confirmed COVID-19 cases still lacked disaggregated data. These data were urgently needed to understand the full impact of the virus on communities of color, and their absence hindered the implementation of sufficient public health measures to mitigate this impact. By October 2020, the CDC reported 299,000 excess deaths, 66 percent of which were attributed to COVID-19 and disproportionately concentrated among Black and Hispanic populations.

“Covid-19 cuts along social lines. Though the virus was once theorized to be the great equalizer — it could take down anyone, no matter how young or rich — that myth was quickly busted. The lines of the disease carved deep into the lives of vulnerable populations to cause unequal pandemic suffering, hitting hardest those who have-not.”

References and further readings

- Simmons, Adelle, et al. “Health disparities by Race and Ethnicity during the COVID-19 pandemic: current evidence and policy approaches.” Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services (2021).

- Khazanchi REvans CTMarcelin JR. Racism, Not Race, Drives Inequity Across the COVID-19 Continuum. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019933. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19933

- https://www.statnews.com/2023/01/30/covid-19-missing-data-race-ethnicity-drive-inequities-decades-to-come/

COVID-19 and Structural Racism

“Racism kills. Whether through force, deprivation, or discrimination, it is a fundamental cause of disease and the strange but familiar root of racial health inequities.” –Reference: On Racism: A New Standard For Publishing On Racial Health Inequities”, Health Affairs Blog, July 2, 2020.

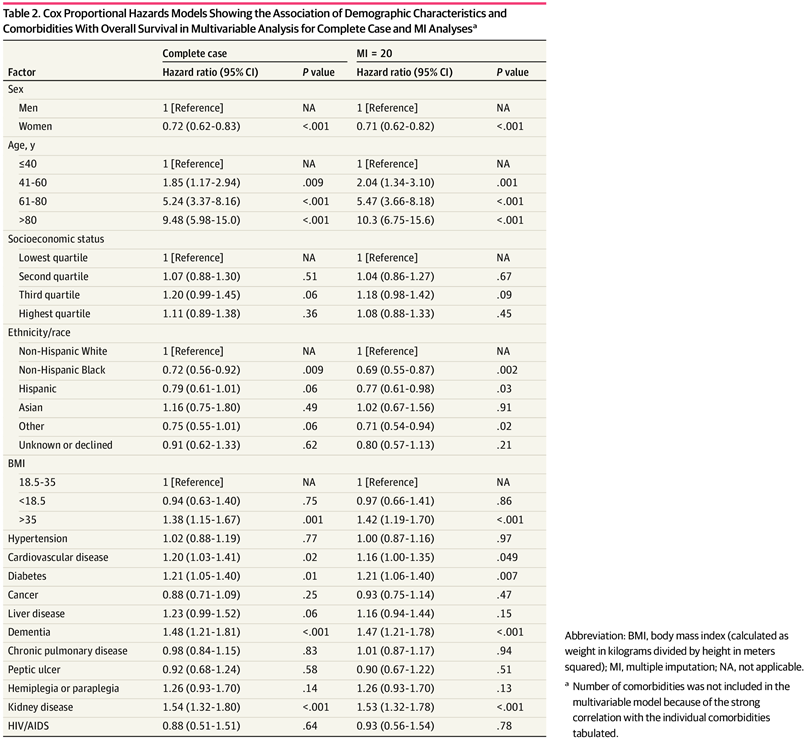

The evidence to date reaffirms that structural racism is a critical driving force behind COVID-19 disparities. Population-level differences in COVID-19 mortality are reflected in disease incidence, prevalence of comorbid conditions, and socioeconomic marginalization among Black and Hispanic individuals. Residential segregation has been identified as a factor mediating racial disparities in COVID-19 cases and mortality rates, as it is closely tied to neighborhood features that shape racial and ethnic health outcomes. Segregated neighborhoods often have high poverty and unemployment rates, poor housing conditions, lower incomes, and limited access to health care and other essential resources.

Studies have found

- High levels of residential segregation between whites and non-whites increase the number of COVID-19 infections in a county, net of other risk factors.

- US counties with a higher proportion of the Black population and a higher proportion of adults with less than a high school diploma had disproportionately higher COVID-19 cases and deaths.

- Areas with high Black populations had higher income inequalities, and percentages of young people (<65 years old) living without health insurance had high rates of COVID-19 mortality.

- Black and Hispanic patients had a higher proportion of more than 2 medical comorbidities and were more likely to test positive for COVID-19 compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts.

COVID-19 has exposed the role that structural racism has played in communities of color for centuries and has exploited these inequities, resulting in higher rates of hospitalization and death in these communities.

References and further readings:

- Yang, Tse-Chuan, Seung-won Emily Choi, and Feinuo Sun. “COVID-19 cases in US counties: roles of racial/ethnic density and residential segregation.” Ethnicity & Health 26.1 (2021): 11-21.

- Lin, Q., Paykin, S., Halpern, D., Martinez-Cardoso, A., & Kolak, M. (2022). Assessment of Structural Barriers and Racial Group Disparities of COVID-19 Mortality With Spatial Analysis. JAMA Network Open, 5(3), e220984. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0984

- Yang, Tse-Chuan, Seung-won Emily Choi, and Feinuo Sun. “COVID-19 cases in US counties: roles of racial/ethnic density and residential segregation.” Ethnicity & Health 26.1 (2021): 11-21.

- Muñoz-Price, L. Silvia, et al. “Racial disparities in incidence and outcomes among patients with COVID-19.” JAMA Network Open 3.9 (2020): e2021892-e2021892.

- Kabarriti, Rafi, et al. “Association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an urban medical center in New York.” JAMA network open 3.9 (2020): e2019795-e2019795.

- Khanijahani, Ahmad. “Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in the United States: a county-level analysis as of November 2020.” Ethnicity & health 26.1 (2021): 22-35.

- Khazanchi, Rohan, Charlesnika T. Evans, and Jasmine R. Marcelin. “Racism, not race, drives inequity across the COVID-19 continuum.” JAMA network open 3.9 (2020): e2019933-e2019933.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos, Wendy L., et al. “Race, healthcare, and health disparities: a critical review and recommendations for advancing health equity.” Western journal of emergency medicine 24.5 (2023): 906.

Dr. Susan Moore’s Story

Dr. Susan Moore died on December 20, 2020, from complications related to COVID-19, two weeks after posting a viral video describing the treatment she received from hospital physicians as racist. As a physician herself, Dr. Moore was forced to advocate for her own care while a White physician dismissed her pain and pleas for help. Despite her medical knowledge and repeated assertions that she could not breathe, as well as her requests for medical tests, she was denied treatment to alleviate the pain and symptoms caused by COVID-19 infection.

Dr. Moore recorded the video (below) to share how poorly she was being treated in the hospital. In it, she stated, “I put forward, and I maintain, if I were White, I wouldn’t have to go through that… This is how Black people get killed, when you send them home and they don’t know how to fight for themselves.” Dr. Moore was released from the hospital, but only twelve hours later she was re-admitted to another facility as her condition worsened rapidly. She ultimately succumbed to complications from COVID-19.

Dr. Moore was an alumnus of the University of Michigan Medical School. Matthew Mixon, a fellow University of Michigan alumnus, stated, “Though I already knew the outcome of her illness, I watched the video again and again. Tears sprang to my eyes as I saw an ill patient crying out for help. Knowing that she was a physician, a fellow alumnus of the University of Michigan Medical School, made her experience even more personal. If she couldn’t advocate and protect herself in the healthcare system, then who could?”

Read More

Anti-Racism and Dr. Susan Moore’s Legacy

Washington Post Opinion: Say Her Name: Dr. Susan Moore

Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Racial and Ethnic Minorities

- Admin (2020) Reps. Pressley, Kelly, Bass, Lee, & sen. Warren introduce legislation to require federal government to collect & release COVID-19 Demographic Data including race and ethnicity, https://pressley.house.gov/. Available at: https://pressley.house.gov/2020/04/14/reps-pressley-kelly-bass-lee-sen-warren-introduce-legislation-require-federal/ (Accessed: 04 October 2024). ↵