15 Weathering and Black Mental Health

Race and ethnicity are associated with many indicators of health status, even after accounting for socioeconomic status, behavior, and other characteristics. Irrespective of income or education level, Black Americans experience poorer health outcomes than White Americans with the same income and education. Poverty alone, therefore, does not fully explain the poor health status of Black Americans. Systematic, persistent, and long-standing discrimination is considered the main contributing factor.[1] [2] Health disparities resulting in chronic morbidity and excess mortality are evident among minorities across all socioeconomic levels and emerge at younger ages than in their White counterparts. While genetics and diet may play a role, they cannot account for this consistency across multiple demographics.

In the early 1990s, public health researcher Arline Geronimus presented an explanation. She observed variations in neonatal mortality showing that infants born to teenage African American mothers had a survival advantage compared with infants born to older African American mothers, and that this variation was more pronounced at older maternal ages. Geronimus posited that the decline in infant survival outcomes was linked to a decline in the health of African American women beginning in early adulthood, resulting from the cumulative impact of repeated exposure to social, economic, and political exclusion. To describe this phenomenon, Geronimus introduced the term “weathering,” referring to the deterioration of the heart, neuroendocrine system, and other body systems that causes minorities to experience accelerated aging. She explained that chronic exposure to stress “weathers” the body, leading to premature aging and poorer health outcomes compared with those not subjected to chronic stress.[3]

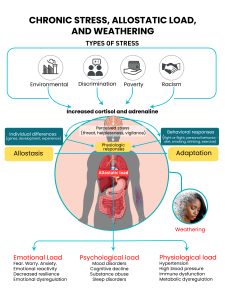

The weathering process is analogous to the way physical structures deteriorate when exposed to harsh environmental conditions over time and is consistent with the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Allostasis refers to the body’s ability to respond and adapt to acute stress to maintain the stable internal state of homeostasis. This process is essential to survival, enabling individuals to adjust to change. However, when allostatic systems are persistently overstimulated by stress and other threats, the repeated demand for adaptation creates an allostatic load that can lead to chronic health conditions, increased morbidity, and premature mortality.[4]

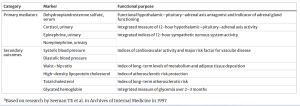

Allostatic load is calculated using biological markers that represent mediators of allostasis (e.g., cortisol, epinephrine, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and norepinephrine), secondary outcomes of allostasis (ie., systolic and diastolic blood pressure, waist-hip ratio, cholesterol, and glycated hemoglobin), and markers that represent biological systems and pathways (cardiovascular, metabolic, inflammatory, and neuroendocrine) that are impacted by allostasis.[5] [6] Thus, allostatic load represents the physiologic and cellular changes that occur due to allostasis and is associated with physical and mental wellness and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

The original 10 markers of allostatic load and their functional purpose[7]

The perception of stress is influenced by one’s experiences, genetics, and behavior. When the brain perceives an experience as stressful, physiological and behavioral responses are initiated, leading to allostasis and adaptation. Over time, allostatic load can accumulate, and repeated exposure to neural, endocrine, and immune stress mediators can have adverse effects on various organ systems, resulting in disease.

A 2006 study revealed that allostatic load scores for Black individuals were statistically significantly higher than the mean scores for White individuals. Among Black participants, women consistently had higher scores than men, whereas scores for White men and women were similar, except in the oldest age group.[9]to stressors such as racism, discrimination, residential segregation, and poverty affects individuals at the cellular level, contributing to a higher prevalence of chronic diseases and poorer health outcomes among Black individuals compared with Whites. This aligns with Geronimus’ Weathering Hypothesis and helps explain why, in comparison to White women, Black women who delay childbirth experience worse birth outcomes. Geronimus notes that older women have likely endured more stress throughout their lifespans and, as a result, have suffered greater health damage. However, she is careful to emphasize that not every Black person experiences more damage than every White person. She states:

“It’s really about how much stress versus social support you get in your everyday life. … Because African Americans and low-income Americans are more likely to suffer more of these stressors, they are more likely to be weathered, weathered severely and weathered at younger ages.” ~ Davies, D. (2023)

~Excerpt from: How poverty and racism ‘weather’ the body, accelerating aging and disease (Accessed: 04 October 2024).

Listen to Dr. Arline Geronimus discuss the weathering hypothesis in detail during her NPR interview with Dave Davies. In the interview, she explains how chronic stress from poverty and discrimination accelerates aging and leads to serious health problems over time, offering a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of social adversity on health.

A 2022 study by Alexis Reeves found that weathering introduces selection bias in research that seeks to recruit disease-free individuals of a certain age.[10] Since minorities experience earlier disease onset, they are often excluded from research samples, which leads to overestimated ages of disease onset. Researcher Alexis Reeves sought to determine how this selection bias affects the estimation of racial and ethnic differences in the age of onset for cardiometabolic outcomes. What she found was striking.

Reeves study revealed:

- Hypertension occurred a median of 5.4 years earlier among Black women and 5.5 years earlier among Hispanic women compared with White women.

- Isolated systolic hypertension was highly prevalent in Black women, with an estimated median age at onset 7.7 years earlier than among White women.

- Metabolic outcomes occurred a median of 11.3 years earlier for Black and Hispanic women compared with White women.

- Addressing all selection mechanisms was associated with a mean 20-year decrease in the estimated median age at onset for all outcomes across racial or ethnic groups.

The results of Reeves’ study suggest that hypertension and metabolic interventions, particularly for Black and Hispanic women, should be targeted as early as age 30 for hypertension and age 40 for metabolic interventions. Ultimately, the study revealed that failing to account for weathering in research recruitment can perpetuate health disparities by excluding minorities from studies designed to identify the ages at which targeted interventions are most effective in preventing chronic disease.

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study was a long-term, multicenter research project that enrolled more than 5,000 Black and White men and women, aged 18 to 30 to examine how cardiovascular disease develops in young adults. Participants were followed for 20 years and assessed for cardiovascular outcomes. Data from the CARDIA study has provided important context for understanding differences in weathering between White and Black individuals and how these differences influence cardiovascular disease.

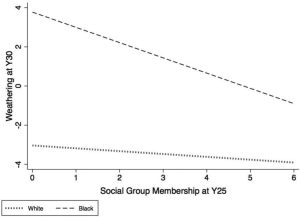

Using CARDIA study data, a 2018 study by Sarah Forrester applied biological age as a measure of weathering and explored its association with psychosocial factors and weathering. Forrester defined weathering as the difference between biological age and chronological age. Positive values indicated that an individual was biologically older than their chronological age, while negative values indicated that an individual was biologically younger.

Forrester found that Black participants had a mean biological age of 57.1 years, compared with 52.3 years for White participants. Mean weathering was 2.6 years for Blacks and -3.5 years for Whites, indicating that at year 30, Blacks had a mean biological age greater than their mean chronological age, while the opposite was observed in Whites. These data suggest that Black adults weathered 6.1 years faster than White adults..[11]

Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo used data from participants enrolled in the CARDIA study to assess the incidence of heart failure over the 20-year follow-up period. The study found that incident heart failure before the age of 50 was 20 times more common in Blacks than in Whites, with the average age of onset being 39 years.[12].

Incident Heart Failure among the White and Black Men and Women in the CARDIA Study.

Kaplan–Meier curves are shown for incident heart failure over the course of 20 years of follow-up in the CARDIA study. The study found that incident heart failure occurred in 27 men and women during the 20-year follow-up, 26 of whom were Black (P = 0.001). The cumulative incidence of heart failure in Black women and men was 1.1 percent and 0.9 percent, respectively, with a mean age of onset of 39 ± 6 years. In contrast, the cumulative incidence of heart failure among White women was 0.08 percent, and among White men it was 0 percent. Heart failure was the cause of death in three Black men and two Black women.

Bibbins-Domingo’s study also revealed that individuals who later developed heart failure frequently had elevated baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressure, obesity, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension before the age of 35. The authors assert that these factors serve as key indicators of increased heart failure risk and underscore the importance of early intervention and preventive strategies.

Reference: Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten, et al. “Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults.” New England Journal of Medicine 360.12 (2009): 1179-1190.

“Racism is not just an added stress to individuals of minority ethnic groups (identified as racial groups) but is a pathogen which generates depression.”

~ Sumam Fernando[13].

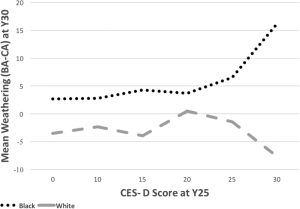

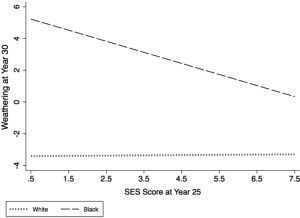

Psychosocial support is critical when accounting for allostatic load, as psychosocial factors are more strongly associated with weathering in Blacks. The previously mentioned study by Forrester[14] assessed symptoms of depression using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (ES-D) to screen for depression in the CARDIA study population. She found that symptoms of depression were associated with higher levels of weathering, and among Blacks only, social participation and socioeconomic status were inversely related to weathering. Although greater social involvement and higher socioeconomic status helped reduce weathering in the Black population, it remained consistently higher than in the White population across these measures.

The above three figures are figures 1-3 from the article: Racial differences in weathering and its associations with psychosocial stress: the CARDIA study.[15]. Forrester’s study also found that Black individuals reported experiencing racial discrimination in at least three domains significantly more often than Whites. Beyond Forrester’s findings, several other studies have documented how racism is driving a mental health crisis and how its effects persist into adulthood.

“The drivers of the mental health crisis for Black children begin early and persist through a lifetime. Black children’s first encounters with racism can start before they are even in school, and Black teenagers report experiencing an average of five instances of racial discrimination per day…Between 1991 and 2019, Black adolescents had the highest increase among any racial or ethnic group in prevalence of suicide attempts — a rise of nearly 80%. About 53% of Black youth experience moderate to severe symptoms of depression, and about 20% said they were exposed to racial trauma often or very often in their life.[16].”

~ Excerpt from: Black kids face racism before they even start school. It’s driving a major mental health crisis

“Expressions of racial hate are ubiquitous in the lives of contemporary Black U.S. American youth for whom the Internet, schools, and neighborhoods serve as contexts in which they are exposed to daily subtle and overt anti-Blackness[17].”

~ Excerpt from: Daily multidimensional racial discrimination among Black U.S. American adolescents

Depression has been linked to both racial discrimination and weathering, and licensed psychologist Dr. Steven Kniffley notes that children of color can begin experiencing race-based traumatic stress as early as ages 4 to 6. Forrester’s study assessing racial differences in weathering found that an increase in symptoms of depression predicts higher biological age, and this association is stronger for Black individuals than for Whites. These early encounters with racism establish a foundation of psychological stress that persists over time and affects Black youth well into adulthood. Early and persistent exposure to racism creates a level of stress and allostatic load that carries into adulthood, producing a burden of disease and health disparities with lifelong negative implications. The cumulative burden of discrimination-driven stressors heightens the vulnerability of Black individuals, leading to premature aging, chronic illness, and related health consequences.

In his article Racism as a Cause of Depression, Sumam Fernando highlights how individuals with depression are often blamed for their condition, with treatment focusing solely on symptoms rather than addressing the deeper, systemic issue of racism as an underlying cause. He emphasizes the need to acknowledge and confront these broader societal factors to provide more effective care.

In the next section, we will outline key strategies for addressing racism at its core, focusing on actionable solutions for systemic change.

- Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. ↵

- American Academy of Family Physicians. “Advancing Health Equity by Addressing the Social Determinants of Health in Family Medicine (Position Paper).” Www.aafp.org, 2019, www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/social-determinants-health-family-medicine-position-paper.html. Accessed 14 Sept. 2024. ↵

- Geronimus, Arline T. "The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations." Ethnicity & disease (1992): 207-221. ↵

- McEwen, Bruce S. "Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load." Annals of the New York academy of sciences 840.1 (1998): 33-44. ↵

- Rodriquez, Erik J., et al. "Allostatic load: importance, markers, and score determination in minority and disparity populations." Journal of Urban Health 96 (2019): 3-11. ↵

- Seeman, Teresa E., et al. "Price of adaptation—allostatic load and its health consequences: MacArthur studies of successful aging." Archives of Internal Medicine 157.19 (1997): 2259-2268. ↵

- Rodriquez, E. J., Kim, E. N., Sumner, A. E., Nápoles, A. M., & Pérez-Stable, E. J. (2019). Allostatic load: importance, markers, and score determination in minority and disparity populations. Journal of Urban Health, 96, 3-11. ↵

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England journal of medicine, 338(3), 171-179. ↵

- Geronimus, Arline T., et al. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States." American journal of public health 96.5 (2006): 826-833. ↵

- Reeves, Alexis, et al. "Study selection bias and racial or ethnic disparities in estimated age at onset of cardiometabolic disease among midlife women in the US." JAMA Network Open 5.11 (2022): e2240665-e2240665. ↵

- Forrester, Sarah, et al. "Racial differences in weathering and its associations with psychosocial stress: The CARDIA study." SSM-population health 7 (2019): 100319. ↵

- Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten, et al. "Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults." New England Journal of Medicine 360.12 (2009): 1179-1190. ↵

- Fernando, S. (1984). Racism as a cause of depression. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 30(1-2), 41-49. ↵

- Forrester, Sarah, et al. "Racial differences in weathering and its associations with psychosocial stress: The CARDIA study." SSM-population health 7 (2019): 100319. ↵

- Forrester, S., Jacobs, D., Zmora, R., Schreiner, P., Roger, V., & Kiefe, C. I. (2019). Racial differences in weathering and its associations with psychosocial stress: the CARDIA study. SSM-population health, 7, 100319. ↵

- Ma, Annie . “Black Kids Face Racism before They Even Start School. It’s Driving a Major Mental Health Crisis.” AP NEWS, 23 May 2023, projects.apnews.com/features/2023/from-birth-to-death/mental-health-black-children-investigation.html. ↵

- English, D., Lambert, S. F., Tynes, B. M., Bowleg, L., Zea, M. C., & Howard, L. C. (2020). Daily multidimensional racial discrimination among Black US American adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 66, 101068. ↵