12 Stuctural Racism and Health

“Structural racism involves interconnected institutions, whose linkages are historically rooted and culturally reinforced. It refers to the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination, through mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, and so on) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources, which together affect the risk of adverse health outcomes.”[1]

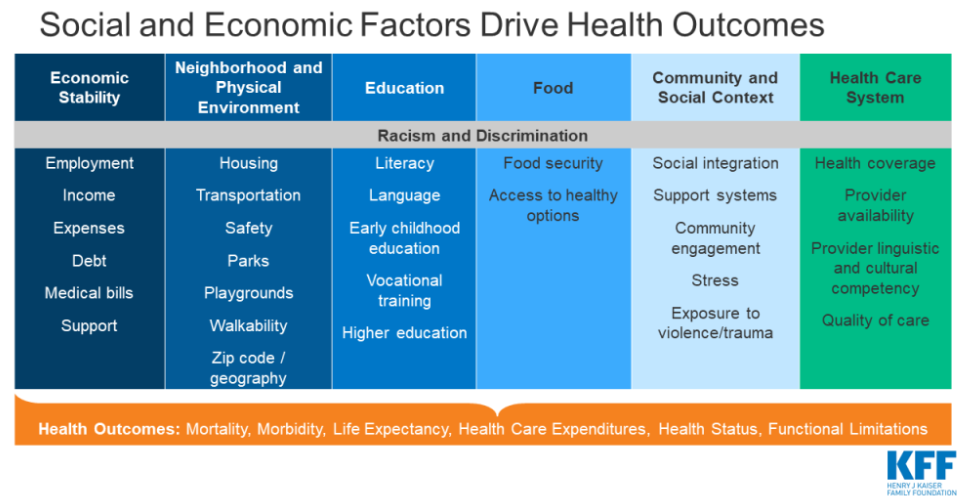

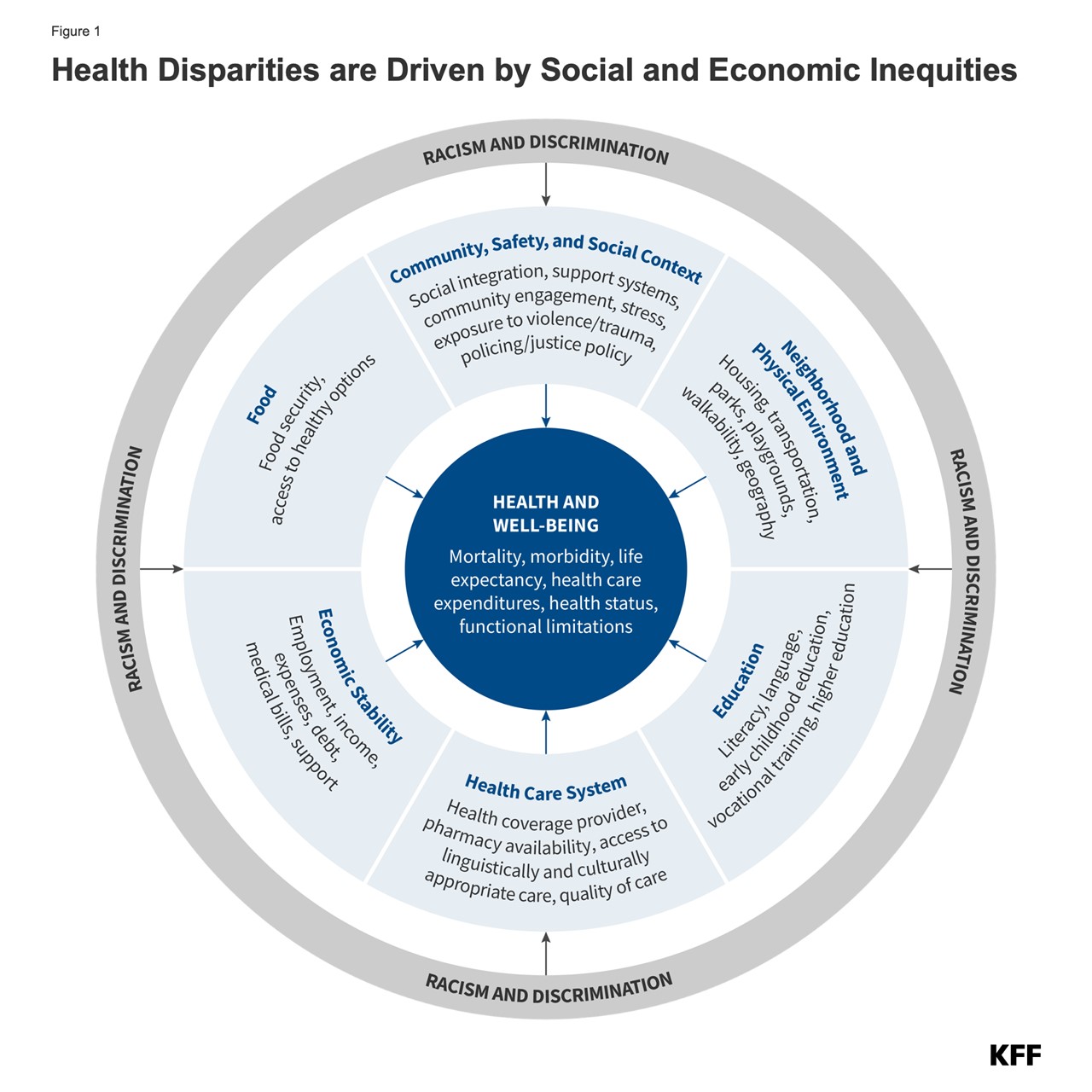

As discussed in Part 2 of this series, disparities in the social determinants of health significantly influence health outcomes and have long been used to explain inequities in communities of color across the United States. Health disparities stem from broader systemic inequities that create structural barriers across multiple sectors of society. Although quality healthcare is critical for good health, the primary drivers of health are the social determinants of health. These determinants are often interrelated and have multigenerational consequences, as children frequently mirror their parents’ circumstances. Children born to parents who have not completed high school are more likely to grow up in environments that negatively impact health, such as unsafe neighborhoods, exposed garbage, and poor-quality housing. They also tend to have less access to sidewalks, parks, playgrounds, recreational facilities, and libraries.[2]

“Health disparities include differences in health outcomes, such as life expectancy, mortality, health status, and prevalence of health conditions. Health care disparities include differences between groups in measures such as health insurance coverage, affordability, access to and use of care, and quality of care. Disparities occur across multiple factors including race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, geography, language, gender, disability status, citizenship status, and sexual identity and orientation. Reflecting the intersectional nature of people’s identities, some individuals experience disparities across multiple dimensions.”[3]

Redlining

“Your zip code is a better predictor of your health than your genetic code.” — Melody S. Goodman, 2014 Pipelines into Biostatistics Annual Symposium

As part of recovery efforts after the Great Depression, the U.S. government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933 to expand homeownership. The HOLC created maps of 239 cities across the United States. To guide mortgage decisions, the agency drew red lines around certain communities and flagged these areas as undesirable, rendering them risky investments for mortgage companies. Although the redlined areas varied in many ways, including the age of the homes, average home values, and proximity to industrial areas, they all shared one common characteristic: Black residents lived there.

Redlining helped perpetuate and validate other racist acts including:

- Restrictive covenants that barred blacks from home ownership

- Undervaluing real estate in black neighborhoods

- Violence against blacks who moved into white neighborhoods

Although redlining ended with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, its impact remains and is evidenced by the lack of investment in these spaces that were once deemed undesirable. Consequently, these areas consistently lack the infrastructure that provides sufficient roads, schools, transportation, employment, and other services on par with that of historically white neighborhoods.

Redlining required the cooperation of several government entities, including banks, private developers, and homeowners. Together, they reinforced the belief that Black residents were undesirable neighbors and that their presence in a community would decrease home values and increase crime.

The racial segregation created by redlining has been a powerful predictor of disadvantage for Black communities, leaving a lasting legacy in which preterm birth, cancer, tuberculosis, maternal depression, and other mental health issues occur at higher rates among residents of once-redlined areas.

References

What is Redlining — NY Times Article

- Bailey, Zinzi D., et al. "Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions." The Lancet 389.10077 (2017): 1453-1463. ↵

- Samantha Artiga Published: Jun 01, 2020 (2021) Health Disparities are a symptom of broader social and economic inequities, KFF. Available at: https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/health-disparities-symptom-broader-social-economic-inequities/ (Accessed: 03 October 2024). ↵

- Nambi Ndugga, D.P. (2024) Disparities in health and health care: 5 key questions and answers, KFF. Available at: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-5-key-question-and-answers/ (Accessed: 03 October 2024). ↵