19 Increase Representation of Underrepresented Minorites

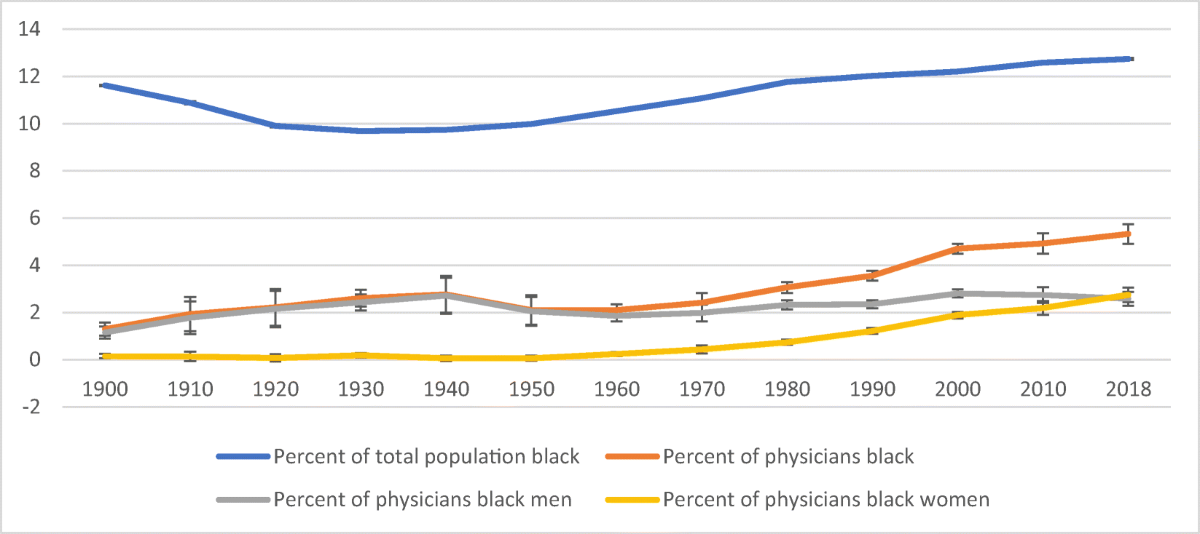

James McCune, the first Black American physician, earned his medical degrees at Glasgow University after facing rejection from U.S. institutions. Returning to the U.S. in 1837, he applied his medical expertise to challenge scientific racism, delivering lectures that refuted phrenology, while also writing extensively on the health and social challenges faced by African Americans.[1] Unfortunately, although more African Americans have been awarded medical degrees from American medical institutions, historically, people of color have been largely excluded from the medical and biomedical fields. The number of Black physicians has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years.[2] Although the percentages of minority healthcare workers are increasing, they remain well below their respective percentages in the general US population.

Percent of physicians and of total population in the USA who are Black, 1900–2018

Percent of physicians and of total population in the USA who are Black, 1900–2018. Author’s calculation using the Decennial Census from 1900 to 2000 and the American Community Survey (ACS) data in 2010 and 2018. All data are publicly available through IPUMS. Results are weighted using Census-provided sampling weights to represent the US population. Occupation and race are self-reported. The bands are 95% confidence intervals.

Recent data from the American Association of Medical Colleges indicates that only 5.7% of US doctors identify as Black, while blacks make up 13% of the U.S. population.[3] The same data show that Hispanics, Native Americans, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders constitute 6.9%, 0.3%, and 0.1%, of the US physician workforce, respectively. A recent study indicated that although the healthcare population is becoming more diverse, people of color are most often in entry-level or low-paying jobs[4]. Although minorities earn 10% of biomedical science PhDs, they represent only 2% of the medical school and basic science teaching faculty[5] (Jr et al., 2014). The diversity of the biomedical workforce is only 13% whereas the percentage in the general population is a combined total of 30%, indicating significant underrepresentation of minorities in these fields.[6] Thus, fostering efforts to increase diversity in the healthcare and biomedical fields is an essential step in the effort to decrease health disparities among people of color.[7]

“The failure to build an adequately trained, diverse STEM workforce in the U.S. that mirrors its shifting demographics will undoubtedly have critical implications on the economic and scientific development of the country.[8] ”

Increase recruitment and retention efforts

Concerted efforts to increase diversity in the healthcare education pipeline are necessary to decrease health disparities. The COVID-19 pandemic concomitant with the death of George Floyd prompted academic institutions to reexamine their diversity efforts and incorporate more intentional efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in the education space. The academic response should be two-pronged, focusing on recruiting and retaining students and faculty of color to foster inclusion and promote belonging in the biomedical fields. Academic institutions have a level of responsibility and accountability to the communities in which they reside; thus there is a critical need for academic institutions to proactively implement efforts to recruit, retain, and train culturally competent biomedical professionals of color. In his presidential address to the Association for the Study of Higher Education, William Zumeta suggested that there is a social contract between higher education and the support of the public the institution is a part of, in that as the needs, values, and expectations of the public change, the institution must adapt and respond accordingly.[9] When significant disparities exist in education, socioeconomic status, and health, academic institutions have a social and moral responsibility to create opportunities that level the playing field for those most affected within their communities. Although achieving health equity is challenging when faced with racial and health disparities, targeted interventions can aid in overcoming these challenges. Academic institutions are well-positioned to improve the pipeline of the biomedical workforce into their communities through intentional efforts of recruitment from these same communities. Data has shown that physicians of color are much more likely than white physicians to practice in underserved communities and treat larger numbers of minority patients.[10] [11] Thus, intentional efforts by academic institutions to recruit and retain underrepresented minorities in STEMM majors can create a positive feedback loop within these communities. This approach helps cultivate culturally competent biomedical and healthcare professionals, driven to improve healthcare access, promote inclusive research, and advocate for policies that enhance health outcomes for underserved populations.

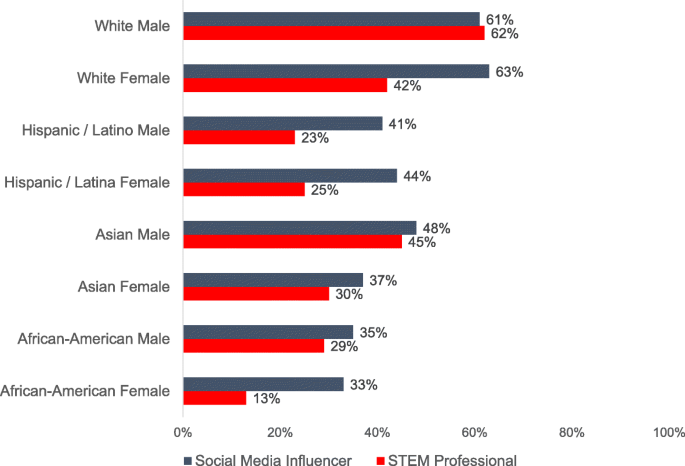

Although minority students are equally likely to enter STEM fields as their white peers, wide gaps exist in the persistence rates of minority students completing their studies in these fields.[12] Many factors contribute to the loss of minority students in these fields, including insufficient pre-college preparation, socioeconomic challenges, limited mentorship, and a lack of belonging. Thus, upon enrollment in higher education, institutions must consistently implement robust retention strategies to prevent the attrition of minority students. The scarcity of people of color in biomedical fields perpetuates the false narrative that individuals from these groups either don’t belong or are unwelcome. In Factors Influencing Participation of Underrepresented Students in STEM fields: Matched Mentors and Mindsets the authors asked participants if they could name STEM professionals of particular gender and ethnicity combinations to understand their familiarity with diverse STEM professionals. Less than a third of the respondents could name a Hispanic or African American STEM professional, but 62% could name a white, male STEM professional. The study authors concluded that “educators should focus on inclusive learning by highlighting the accomplishments of diverse STEM professionals, to help strengthen feelings of STEM belonging.” In addition to inclusive teaching, institutions of higher education must also seek to increase the minority faculty pool, providing culturally competent mentors and helping to change an academic culture that is predominately white and male. Inclusive teaching and increasing diversity among biomedical faculty help minority students see individuals who share their backgrounds succeeding in STEM, challenging ingrained stereotypes and affirming that STEM fields are not exclusive to a single group. These efforts fortify retention efforts, increasing persistence in STEM and assisting in closing the representation gap within these fields.

Studies have shown that increasing diversity in healthcare fields can drive health equity initiatives, resulting in better health outcomes in minority communities.[13] A 2023 study revealed a significant underrepresentation of Black primary care physicians (PCPs) compared to the Black population. It also found that U.S. counties with a higher percentage of Black PCPs saw improved health outcomes for the Black community, including increased life expectancy and reduced disparities in health between Black and White populations.[14] Racial concordance between patients and physicians has also been linked to improvements in the mortality of black infants.[15] Studies assessing racial concordance between doctors and patients have shown that patients communicate better and more thoroughly during interactions and are more compliant with medical advice.[16]

A diverse health and biomedical workforce benefits patient care and influences healthcare policy and institutional practices in meaningful ways. Promoting minority healthcare professionals into leadership roles ensures that diverse voices are present in decision-making processes at hospitals, clinics, and healthcare organizations. Increased minority representation in these fields has a broader influence on health policy development and implementation, as minority healthcare professionals can be powerful advocates for policies that improve healthcare access and health outcomes in minority populations. Additionally, they can help push for policy reforms and training to reduce bias and amplify the minority voice and experience in research endeavors. Increased minority representation in leadership positions can help drive changes that dismantle structural racism and expand support programs to strengthen the pipeline of minority enrollment in healthcare-related fields. Moreover, increasing diversity in medical and biomedical leadership can help ensure that medical education is inclusive and free from harmful stereotypes, and aid in creating a more culturally sensitive healthcare workforce. These efforts will foster a continuous cycle that boosts minority representation in STEM fields, driving innovation and bringing us closer to achieving racial health equity.

- Morgan TM. The education and medical practice of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865), first black American to hold a medical degree. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003 Jul;95(7):603-14. PMID: 12911258; PMCID: PMC2594637. ↵

- Ly, Dan P. "Historical trends in the representativeness and incomes of Black physicians, 1900–2018." Journal of General Internal Medicine 37.5 (2022): 1310-1312. ↵

- Physician Specialty Data Report. (n.d.). AAMC. Retrieved September 30, 2024, from https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/physician-specialty-data-report ↵

- Wilbur, K., Snyder, C., Essary, A. C., Reddy, S., Will, K. K., & Mary Saxon. (2020). Developing Workforce Diversity in the Health Professions: A Social Justice Perspective. Health Professions Education, 6(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2020.01.002 ↵

- Jr, K. D. G., McGready, J., Bennett, J. C., & Griffin, K. (2014). Biomedical Science Ph.D. Career Interest Patterns by Race/Ethnicity and Gender. PLOS ONE, 9(12), e114736. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114736 ↵

- Wilson, M. A., DePass, A. L., & Bean, A. J. (2018). Institutional Interventions That Remove Barriers to Recruit and Retain Diverse Biomedical PhD Students. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 17(2), ar27. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-09-0210 ↵

- Peek, M. E. (2023). Increasing Representation of Black Primary Care Physicians—A Critical Strategy to Advance Racial Health Equity. JAMA Network Open, 6(4), e236678. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6678 ↵

- Ghazzawi, Dina, Donna Pattison, and Catherine Horn. "Persistence of underrepresented minorities in STEM fields: Are summer bridge programs sufficient?." Frontiers in education. Vol. 6. Frontiers Media SA, 2021. ↵

- Zumeta, W. M. (2011). What Does It Mean to Be Accountable?: Dimensions and Implications of Higher Education’s Public Accountability. The Review of Higher Education, 35(1), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2011.0037 ↵

- Cohen, Jordan J., Barbara A. Gabriel, and Charles Terrell. "The case for diversity in the health care workforce." Health affairs 21.5 (2002): 90-102. ↵

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA. The Racial and Ethnic Composition and Distribution of Primary Care Physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):556-570. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036. PMID: 29503317; PMCID: PMC5871929. ↵

- Ghazzawi, Dina, Donna Pattison, and Catherine Horn. "Persistence of underrepresented minorities in STEM fields: Are summer bridge programs sufficient?." Frontiers in education. Vol. 6. Frontiers Media SA, 2021. ↵

- Peek, M. E. (2023). Increasing Representation of Black Primary Care Physicians—A Critical Strategy to Advance Racial Health Equity. JAMA Network Open, 6(4), e236678. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6678 ↵

- Snyder JE, Upton RD, Hassett TC, Lee H, Nouri Z, Dill M. Black Representation in the Primary Care Physician Workforce and Its Association With Population Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e236687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6687 ↵

- Greenwood, Brad N., et al. "Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117.35 (2020): 21194-21200. ↵

- https://www.aamc.org/news/do-black-patients-fare-better-black-doctors ↵