2 A Brief History of Belize

Esri, CGAIR, USGS, CONANP, Esri, HERE, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS

Visit the open access interactive Belize StoryMap resource on the University of Cincinnati Press Imagining Central America Manifold page to enhance your experience of this chapter.

INTRODUCTION

Known as British Honduras until 1973, Belize is the only Central American country to have been primarily colonized by the British. It is also the only Central American country whose official language is English rather than Spanish; additionally, a form of English Creole, known as Belizean Kriol, is also widely spoken. Belize’s population is a mix of mestizos (descendants of Spanish settlers and Indigenous Maya), Indigenous Maya, Creoles (descendants of African slaves and English settlers), the Afro-Indigenous group called the Garifuna, Asians (especially Taiwanese and Chinese), and Europeans. The Belizean economy was historically built around mahogany extraction, and a likeness of the tree is featured on the Belizean flag.

Belize has a strained relationship with neighboring country Guatemala, the government of which frequently claims that Belize is Guatemalan territory. This tension has lasted for over a hundred and fifty years and continues today.

TIMELINE OF KEY EVENTS

1508: First known date of Spanish presence; Mayan communities resist Spanish attempts at control of region

1546: Mayan uprising that forcefully expelled the Spanish from Belize

1638: The Baymen (British and Scottish pirates) arrive to Belize coast

1650s: Estimated date of British settlement

1698: Spanish give up attempts to claim Belize, leaving the area

1717–1779: Spanish forces stage various attacks against British settlers

1798: British defeat Spanish in Battle of St. George’s Caye

1838: Enslaved people emancipated

1839: Central American Federation disintegrates; Guatemala claims Belize as its territory—Belize was not part of the Federation

1859: Great Britain and Guatemala sign agreement in which Guatemala promises to rescind claims to Belize in exchange for road construction from Guatemala City to Caribbean coast

1862: Belize officially declared a colony of the British Commonwealth, named British Honduras

1893: Mariscal-Spender Treaty delimits border between Mexico and Belize

1945: Belize designated as the 23rd department in Guatemala’s new constitution

1949: People’s Committee formed to protest devaluation of British Honduran dollar

1950: People’s United Party (PUP) formed; minimum age for women voters lowered from 30 to 21

1954: New constitution created that gives Belize full political autonomy, universal adult suffrage, and a two-chamber parliament

1970: Belmopan replaces Belize City as capital

1973: Country officially changes its name from British Honduras to Belize

1981: Belize gains independence from Great Britain with George Price as prime minister; the country remains part of the Commonwealth

1984: First elections since independence; United Democratic Party leader Manuel Esquivel wins

1993: British government announces withdrawal of troops and an end to security guarantee

2005: Unrest caused by tax increases

2008: Dean Barrow elected Belize’s first Black prime minister

2012: Dean Barrow re-elected

2018: Referendums held in both Guatemala and Belize to send Belize-Guatemala border dispute to International Court of Justice

2019: International Court of Justice officially presented with Belize-Guatemala border dispute case

2020: Johnny Briceño of the People’s United Party becomes prime minister

2021: Froyla Tzalam nominated Governor-General of Belize, becoming first Indigenous Governor-General in Belize

A HISTORY OF BELIZE

Pre-Columbian Era

Belize, a small nation on the Caribbean coast of Central America, occupies part of the territory in which the Maya civilization flourished during the first millennium [BCE], with an apogee in the Classic Period of 250–900 [BCE].[1]

Prior to the arrival of European colonial powers, Belize was populated by Indigenous groups, particularly the Maya, whose territory extended into present-day Belize’s neighbor, Guatemala. At around 850 BCE, it was a thriving region, hosting a population of over three hundred thousand in different city-states throughout much of the present-day country. Maya civilization was mostly agricultural, including crops such as corn and squash, as well as hunting and fishing activities; craft skills such as pottery and jade-carving became popular later. There was some tension and fighting between the different Maya groups: in 1123 BCE, the Yucatec Maya of the north rose up and overthrew the Itzá Maya from the Petén Basin, a region that stretched from northern Guatemala to southeastern México. The other two significant Maya groups were—and still are—the Q’eqchi’ and the Mopan.

There are several Maya sites that can be visited throughout the country, such as Altún Ha near present-day Belize City and Xunantunich in Cayo, which is the tallest human-made structure in Belize. Altún Ha was settled around 200 BCE and became a hub of activity, with almost ten thousand people living there. Altún Ha is home to several temples and buildings where priests lived. It is speculated that a peasant uprising took place against the ruling priest class. Xunantunich—which means “Lady of the Rock”—was settled in 300 BCE and boasted fertile lands that were good for farming. Maya civilization declined greatly during the eighth and ninth centuries, their population diminishing significantly. There are many theories as to why this happened, including the spread of disease, droughts devastating the Yucatán and Petén areas, and competition between different city-states.

Colonization and English Rule

What we today call Belize was in the seventeenth century a remote backwater that attracted British pirates and buccaneers as a base from which to raid ships headed to Spain with their valuable (and typically imaginary) cargoes of gold. The watery lowlands of central and northern Belize were also, however, home to dense stands of logwood, which in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries became a highly valuable commodity—a source of dye for the burgeoning textile industry in England. Some of the early privateers settled in these waterlogged plains, cutting and selling logwood as a means to generating wealth.[2]

Unlike the rest of Central America, Belize’s colonizers were from Great Britain rather than Spain. This was mostly due to the Spanish focus on other parts of the region for extraction and development; the Spanish had been the first European presence in Belize, starting excursions in 1508 and later officially declaring conquest in 1542. They were aggressively resisted by the Maya, and were thrown out during a massive uprising in 1546. The Spanish made various attempts to get control of the region, staging several raids against the Maya, destroying their villages and anything to do with Mayan cultural identity.

In 1638, British and Scottish pirates—known as the Baymen—arrived to the coast of Belize in an effort to find a secluded area from which they could attack Spanish ships. The presence of the Baymen on the coast caused the Maya to flee inland. The Baymen settled the coast and soon discovered a sustainable living in cutting, selling, and exporting logwood—a tropical tree found throughout southern Mexico and northern Central America, whose heartwood was used to make a purple-red dye in addition to using the wood for craftsmanship—from Belize to England. The Baymen then introduced slavery to the region in order to support this budding industry, eventually bringing enslaved Africans from the West Indies.

A 1667 treaty in England calling for the suppression of piracy only encouraged the growth of this new logging industry. In 1670, the Godolphin Treaty between England and Spain confirmed English claim to all countries and islands in the Western hemisphere that England had already settled; however, this treaty did not name the coastal area between Yucatán and Nicaragua, where Belize lay. Contention between the European countries continued until 1717 when Spain expelled British loggers from the Bay of Campeche, west of Yucatán. This action had the unanticipated effect of a llowing the British settlement near the Belize River to continue growing.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the Spanish attacked the British settlers continuously, forcing them to leave the area on four occasions: in 1717, 1730, 1754, and 1779. In spite of this, the Spanish never officially settled the region, and consequently the British always returned to expand their own trade and settlement. The Battle of St. George’s Caye in 1798 was the final Spanish attack against the British settlement in which Spanish governor General Arturo O’Neill led a flotilla of thirty vessels and two thousand troops against the Spanish. The British eventually won the engagement, officially expelling the Spanish from claiming control of the area that comprises Belize today. “[T]he British tried, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, to secure Belize as a colony away from the Spanish and ‘to wipe out all memory of Spanish pretensions, and to encourage exclusively the British way of life’. One of the first outward and visible signs of a British colony in those days was the establishment of the National Church.”[3]

British colonialism focused on “extractionism”: the practice of systematically identifying and extracting valuable natural resources on a massive scale for capital benefit. The British identified resource-rich land and established colonies in order to extend the reach of the British empire. This method of “indirect colonialism” formed a world-wide network of trade ports and taxable states that benefited the crown, while not demanding a large contingent of settlers.[4]

The British shifted their economic focus from logwood to mahogany extraction near the end of the eighteenth century. While the extraction of logwood was less labor intensive, the mahogany industry demanded more money and land, and consequently more laborers to work that land. Enslaved people in Belize were officially emancipated in 1838, five years after the British Slave Emancipation Act was passed. This put a strain on the growing mahogany industry, and the British found ways to make up for the labor that had been lost upon emancipation: “At the time of emancipation, a boom in the mahogany market created a need for labor, which was dealt with by importing indentured labor and using coercive methods to keep freedmen dependent.”[5]

The Garifuna—also known as the Garinagu, an Afro-Indigenous people descended from the Carib people of the Caribbean and Africans who had escaped from slavery and resisted colonialism in the Lesser Antilles—arrived to southern Belize by way of Honduras, reportedly as early as 1802. They settled in the Stann Creek area and became fisherfolk and farmers. Other Garifuna arrived to Belize after a civil war in Honduras in 1832. November 19, 1832, is the date officially recognized as “Garifuna Settlement Day” in Belize, which is celebrated nationally and regionally throughout Central America by Garifuna communities.

In 1854, Britain laid an official claim to the settlement they had established in Belize, shortly following concessions they had made regarding the Bay Islands and the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua. The Settlement of Belize in the Bay of Honduras was declared a British colony in 1862, officially dubbed British Honduras and put under the governance of the British leaders in Jamaica, another British colony in the Caribbean.

Independence

Belize gained its political independence in September 1981 from the United Kingdom to become the 156th member of the United Nations, a separate member of the British Commonwealth of Nations, as well as an individual member of what [Keith] Buchanan terms the “commonwealth of poverty”—the Third World. Belize is definitely a “Caribbean society” as defined by [David] Lowenthal, although its location on the mainland of Central America has meant that the country’s history is very much interwoven with this landmass as well.[6]

The British Honduran economy remained heavily reliant on mahogany extraction, especially due to the interests of investors such as the British-owned Belize Estate and Produce Company, which at one point owned half of all privately-held land. This proved to be detrimental when the Great Depression hit, nearly causing the colony’s economy to collapse as British demand for timber plummeted. The damage was exacerbated when a category four hurricane hit Belize in 1931, the deadliest in the country’s recorded history. Belize City, the capital, was ravaged.

Conditions worsened further when Britain decided to devalue the British Honduran dollar in 1949. Popular mobilization had been stirring in the wake of the 1931 hurricane because of the lack of government support; the devaluation finally encouraged British Hondurans to organize for the founding of the first local political party, the People’s Committee, which would then become the People’s United Party (PUP). The PUP protests against devaluation eventually became a campaign demanding independence from Britain, as well as constitutional reforms such as expansion of voting rights to all adults. The colonial government granted universal adult suffrage in 1954, and the first election was decisively won by the PUP. Pro-independence activist George Price became the PUP leader in 1956 and the head of government in 1961. Britain proclaimed “self-government” for Belize in 1964, under a new constitution.[7] In June of 1973, British Honduras was renamed Belize. Although there is no official account of why the name “Belize” was chosen, there are several theories, including that it may derive from a Maya word: possibly “Balix,” meaning “muddy waters” in reference to the Belize River, or perhaps “Belikin,” meaning “land facing the sea.”

Under Prime Minister George Price, Belize began a campaign for full independence, seeking international recognition as a nation. The first United Nations resolution supporting independence for Belize was passed in 1975, with 110 votes in favor, 16 abstentions, and only 9 against; however, none of the Spanish-speaking Latin American countries voted in favor, apart from Cuba. Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Uruguay all voted no, and the rest abstained. The Central American nations likely voted “no” out of respect for Guatemala and its claims to Belize’s territory. Prime Minister Price met with General Omar Torrijos, president of Panama, at the 1976 summit meeting of the Non-Aligned Nations—a group formed in the 1950s in response to the increasingly polarized Cold War-era world of 120 states from the Global South that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc, and which still functions as a major international organization today. PM Price’s meeting with General Torrijos was an effort to gain the Panamanian government’s support for Belizean independence. The Sandinista government of Nicaragua was a major supporter of Belize’s bid for independence. By the end of 1980, Belize had gained nearly unanimous international support, and officially gained its independence from Britain on September 21, 1981, almost two hundred years later than the rest of Central America.[8]

Present-Day Belize

In 1984, heads of state of the CARICOM countries (the Caribbean Community and Common Market), including Belize, met in the Bahamas to affirm economic policies contained in the “Nassau Understanding.” This statement committed the region to diversifying its exports away from a handful of agricultural commodities (such as sugar) that had experienced deep declines in world prices in the early 1980s. Caribbean governments pledged to adopt nontraditional crops and attract offshore manufacturing from the United States and Europe in order to cushion themselves against volatile monocrop markets.[9]

Under Prime Minister George Price, the People’s United Party continued to win elections until 1984, which was the first national election since Belize’s independence. In the 1984 elections, the PUP lost to the United Democratic Party (UDP), led by Manuel Esquivel, who succeeded Price as prime minister. In 1985, Prime Minister Esquivel signed an agreement with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), requiring the Belizean government to adopt neoliberal, structural adjustment, economic policies, such as the privatization of state corporations.

The UDP and the PUP continue to dominate Belize’s political scene, trading power back and forth across the years. UDP leader Dean Barrow became prime minister in 2008 after a landslide victory in the general elections, with the UDP winning 25 out of 31 seats in the House of Representatives. He was re-elected in 2012. In November of 2020, the PUP defeated the UDP for the first time since 2003, and PUP party leader Johnny Briceño became prime minister. In April 2021, Froyla Tzalam, a Mopan Maya community leader, was nominated to be the Governor-General of Belize. The Governor-General serves as Commander-in-Chief of the Belize Defence Force in addition to being a general representative of the country. Tzalam is the second woman and the first Indigenous person to serve as Governor-General.

In the context of the international community, Belize has continued to have a unique position, difficult to fit in any one regional or cultural community. Indeed, there continues to be a question over whether Belize ought to be considered more a Caribbean country rather than a member of Central America. Its membership in the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) only underscores this issue. Belize shares many cultural similarities to Caribbean countries, as well as the historical legacy of being subject to British rather than Spanish colonization. In fact, there is large overlap between those countries who have membership in CARICOM and countries that are, or historically have been, part of the English Commonwealth. CARICOM itself began to emerge after the collapse of British West Indies Federation in 1962; the project for Caribbean integration was initiated in 1965 by the creation of the Caribbean Free Trade Area.[10] Still, Belize also became a full member of the Central American Integration System (SICA) in 1998, so its membership in CARICOM does not necessarily align its identity with the Caribbean community exclusively.

Belize also has the highest Black/Afro-descendant population in the Central American region, with 32 percent of its citizens self-identifying as such.[11] This demographic difference sets Belize apart from most of the other Central American countries, whose populations are primarily mestizo and Indigenous. The presence of the Garifuna, an Afro-Indigenous people, certainly play a role in this larger conceptualization of Belize’s national identity, both as an Afrodiasporic country and as a Caribbean country, given the Garifuna’s intertwined African and Caribbean cultural heritage.[12]

Tourism in Belize

Cultures have been subsumed, ritualised for the benefit of hordes of camera-wielding, high-spending, experience-seeking people from well-heeled countries anxious to capture every moment on flim.[13]

Although the agricultural sector remains Belize’s primary source of income, the tourism industry has quickly become a dominating force in the country’s economy, particularly “ecotourism.” Key and Pillai define ecotourism as “traveling to an undisturbed and pristine natural environment with the object of studying, admiring and enjoying the scenery with its wild plants and animals.”[14] Essentially, Belize’s natural biodiversity has become its primary commodity. Many present-day tourists travel to countries like Belize in pursuit of “the authentic.” While tourism has indeed been an important factor in Belize’s modern economic development, there are also concerns over the sustainability of this model, particularly because of tourists’ impact on the environment. The increase in tourism has led to the construction of bars, restaurants, and hotels to host foreign visitors. The land is cleared, trees cut, and other natural resources depleted for the sake of accommodating the tourist industry.[15] However, as the question of sustainability comes to the forefront, the government of Belize has begun grappling with how to find a balance between ensuring the sustainability of the environment of Belize and the continued success of the tourism industry.

Though there is certainly a significant benefit to the national economy, on a local level, there is a bit more conflict and nuance to the tourist-host relationship. Some Belizeans maintain a positive view of the industry’s effects on local economies, appreciative of the jobs it creates and the opportunities it provides. Still others see the way that an emphasis on tourism has shifted the culture of their communities, enticing “fisherman to take out tourists rather than fish” and barring locals from interacting with the land in ways they have done for generations, such as frequenting beaches that are now closed off as private property.[16]

Social Movements

During popular debates held before independence was achieved in 1981, Garifuna women and men were popular theorists and social spokespersons in favour of the idea that independence politics was going to be the backbone of a new multiethnic and multicultural political entity. Women expressed their views on several occasions, that independence was not only good news for the rights of the Garifuna but also for other ethnic groups established in Belize.[17]

The Garifuna have faced prejudice in Central America; their unique history and cultural expressions set them apart from much of the region, and it is an enduring struggle for this group to retain their identity and dignity. One of the ways that the Garifuna have begun to center their cultural identity is by changing the name of one of their major settlements in the country: sometime in the early 1800s, Garifuna from Honduras traveled north to Belize, where they settled in what became known as Stann Creek Town, the capital of Belize’s Stann Creek District. Around 1975, however, Stann Creek Town’s name was changed to Dangriga, a Garifuna word that means “standing waters.” Dangriga is known as Belize’s “cultural capital” for its concentration of Garifuna cultural expressions, particularly punta music.

Maya culture and identity, like the Garifuna, persist today; their most tangible influence is in the momentum of the land rights movement in Belize. Arguably, traction has been gained for this movement in response to an increase in tourism and a renewed sense of responsibility to be stewards of their country in the face of land lost to hotels and ex-pat housing development. One of the turning points regarding both land rights activism and the persistence of Indigenous identity was in April 2015, when the Maya people of Belize’s Toledo district won a landmark case in the Caribbean Court of Justice. The Q’eqchi’ and Mopan Maya had been fighting for rights to their historical lands for decades. The Caribbean Court of Justice, Belize’s highest appellate court, judged that the land be demarcated and registered to the Maya; that damages be awarded to the Maya people to compensate for all material and moral harm inflicted; and that the government of Belize cease and desist all destruction and use of the designated land without first getting the informed consent of the Indigenous population.

Although the government has not always honored this ruling, now the Indigenous communities of Belize have the legal right to confront the wrongdoings of officials. In September 2021, the Garifuna Nation condemned the government for encroaching on Garifuna settlements in the south. The Nation accused the government of constructing a gas station in Seine Bight without consulting the local Garifuna people. Garifuna lands in Belize are not, at the time of writing, demarcated as Maya lands are; however, in light of the government’s attempt to construct on Garifuna lands without their consent, the knowledge of legal precedent in the country has encouraged many in the community to stage protests.

Border Dispute with Guatemala

Guatemala’s controversial claim to the territory of Belize, the roots of which lie in a vaguely worded treaty from 1859 between Guatemala and Great Britain, has not only hindered the political development of Belize, but has affected relations between the United States and Britain, and Central America and the Caribbean. Because of the unequal size and might of the two nations, Belize has found it necessary to maintain the military protection of the British government, even though it is now an independent nation.[18]

Unlike many Central American countries who have faced internal strife, often to the point of civil war, Belize’s most heated point of contention lies with its neighbor, Guatemala. For over a hundred and fifty years, Guatemala has laid claims to its neighbor’s territory; often, maps drawn by the Guatemalan government show Belize as Guatemala’s twenty-third department. When the Spanish empire disintegrated in the 1820s, the independent republics that would eventually become Mexico and Guatemala both made claims to the Belizean territory. However, as these claims were made under the 1786 Convention of London—a doctrine applied specifically to Spain and Spanish territories—Britain, the nation that had settled Belize, did not recognize those claims. Mexico eventually dropped its claims, but Guatemala did not.

In 1859, the Wyke-Aycinena Treaty was written, wherein Guatemala agreed to recognize British Honduras (Belize) as a British colony, conceding all supposed “sovereign rights” in exchange for Great Britain’s commitment to build a road from Guatemala City to the Belizean town of Punta Gorda, on the Caribbean coast. But an issue arose with the treaty: “While it is clear that Britain and Guatemala agreed to build a road, the phrase used in the treaty, ‘mutually agree conjointly,’ left unresolved whether Britain was to build the road entirely at its expense.”[19] When the treaty was later ratified, Britain claimed that it was released from any obligation to build the road, as well as denying Guatemala’s entitlement to Belize. The dispute over this part of the treaty persisted until 1940, when Guatemala “stated that it was no longer a question of whether Article Seven [the disputed section] could be fulfilled. Guatemala now had the right to recovered territory ‘ceded’ in 1859.”[20] Guatemala then created a new constitution in 1945, where it was stated that “any efforts taken towards obtaining Belize’s reinstatement to the [Guatemalan] Republic are of national interest.”[21]

At the beginning of 1948, Guatemala threatened to invade Belize in order to forcibly annex what they claimed was rightfully theirs. The British, who still protected Belize as their territory and colony, deployed two companies from a British battalion, with one company sent to investigate the border. Although they did not see any evidence of an imminent Guatemalan invasion, the British stationed a company in Belize City just to be safe. Great Britain and Guatemala attempted diplomatic talks between 1961 and 1975, breaking off intermittently as Guatemala continued to issue threats of invasion, as well as occasionally sending troops to the disputed border as a form of intimidation. In 1978, the British proposed an agreement to adjust the territorial boundaries; to this, Prime Minister Price declared, “We will not cede as much as one centimetre of Belize to Guatemala or anyone else!”[22]

When Prime Minister Price met with President Torrijos of Panama during the 1976 Non-Aligned Nations summit about Belize’s pending independence, the Guatemalan government broke off relations with Panama.[23] When Belize gained its independence from Britain in 1981, Guatemala did not recognize its nationhood, continuing to claim Belize as Guatemalan territory. Again, about 1,500 British troops were stationed in Belize to prevent any potential invasions; this put stress on the nation’s population, as “the continued presence of British military forces, made necessary by Guatemala’s irredentist claims, was a painful reminder of the new nation’s dependence.”[24]

The year of Belize’s independence, Prime Minister Price and the PUP government offered several concessions to Guatemala in exchange for dropping its territorial claims, including a sea corridor through Belizean waters, granting access to the Caribbean; passage for pipelines to carry Guatemalan oil to terminals on the Caribbean; and the construction of a road that crosses from the Guatemalan frontier to the coast. However, PUP’s opponents, the UDP, attacked the deal, and it was eventually dropped completely.[25]

In 1991, the Government of Guatemala released a statement saying that they recognized Belize’s independence, and the two countries were finally able to establish diplomatic relations, with an ultimate goal of settling the territorial dispute. However, in 1999, Guatemala sent a message to Belize stating that, while they did recognize Belize’s sovereign nationhood and right to self-determination, Guatemala would still be laying claim to the land that Belize was occupying.

Guatemalan president Jimmy Morales was vocally supportive of Guatemala’s claim to Belize. A referendum was held in April 2018 by the Guatemalan government to determine whether to send the territory claim to the International Court of Justice (ICJ)—95.88 percent of voters voted in support of sending the claim, with 25 percent voter turnout. In May 2019, Belize held its own referendum, and just over 55 percent of voters voted in favor of sending the dispute forward. Based on both of these results, in June 2019, the International Court of Justice received the request to resolve the dispute. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the timeline for addressing the case has been in flux, but as of writing this chapter, prepared briefs from each country in defense of their positions will be due in summer of 2022. Then the ICJ will move forward with determining how to settle this centuries-old territorial dispute.

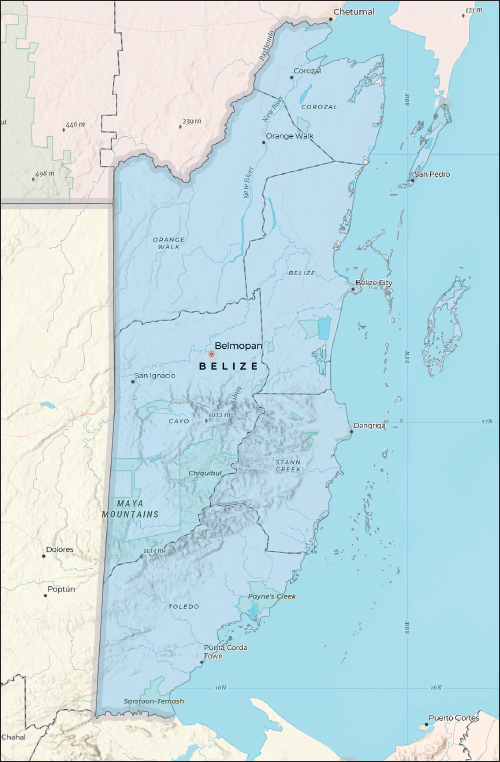

THERRITORIAL CLAIMS MAP (TRANSLATION)

This map illustrates the territory that Guatemala claims from Belize and the adjacency line.

- Guatemala claims 12,722 km² of land and 100 km² of the islands from Belize

- For more than 150 years, Guatemala has maintained the territorial dispute

- Belize’s governmental system is a constitutional monarchy. It has a prime minister.

- Agriculture is their primary activity; after that is fishing, construction, transportation, and tourism.

- Belize represents 0.74 percent of the total population of Central America. Approximately 311,000 inhabitants.

- Belize’s economy occupies the last place among the seven countries of the isthmus.

- Their official language is English, but a large part of the territory speaks Creole or “Kriol.” The currency is the Belizean dollar

Recommended Reading

Bolland, O. Nigel. Colonialism and Resistance in Belize: Essays in Historical Sociology. Belize City: Cubola, 1988.

Bulmer-Thomas, Barbara, and Victor Bulmer-Thomas. The Economic History of Belize from the Seventeenth Century to Post-Independence. Belize: Cubola Books, 2012.

Campbell, Mavis C. Becoming Belize: A History of an Outpost of Empire Searching for Identity, 1528–1823. Kingston: University of West Indies Press, 2011.

Dobson, Narda. The History of Belize. London: Longman Caribbean Limited, 1973.

Durán, Víctor Manuel. An Anthology of Belizean Literature: English, Creole, Spanish, Garifuna. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2007.

Edgell, Zee. Beka Lamb. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2015.

Macpherson, Anne. From Colony to Nation: Women Activists and the Gendering Politics in Belize, 1912–1982. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

McClaurin, Irma. Women of Belize: Gender and Change in Central America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Shoman, Assad. Belize’s Independence and Decolonization in Latin America: Guatemala, Britain, and the UN. 1st ed. Studies of the Americas. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Shoman, Assad. Thirteen Chapters of a History of Belize. Belize City: Angelus Press, 1994.

- Norman Hammond, “The Prehistory of Belize,” Journal of Field Archaeology 9, no. 3 (1982): 1. ↵

- Melissa A. Johnson, “The Making of Race and Place in Nineteenth-Century British Honduras,” Environmental History 8, no. 4 (2003): 600. ↵

- Nancy Lundgren, “Children, Race, and Inequality: The Colonial Legacy in Belize,” Journal of Black Studies 23, no.1 (1992): 100. ↵

- Matthew Lange, James Mahoney, and Matthias Vom Hau, “Colonialism and Development: A Comparative Analysis of Spanish and British Colonies,” American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 5 (2006): 1427, https://doi.org/10.1086/499510 ↵

- Lundgren, “Children, Race, and Inequality,” 93. ↵

- John C. Everitt, “The Torch is Passed: Neocolonialism in Belize,” Caribbean Quarterly 33, no. 3/4 (1987): 44. ↵

- Elisabeth Cunin and Odile Hoffmann, “From Colonial Domination to the Making of the Nation: Ethno-Racial Categories in Censuses and Reports and their Political Uses in Belize, 19th–20th Centuries,” Caribbean Studies 4, no.2 (2013): 44. ↵

- Alma H. Young and Dennis H. Young, “The Impact of the Anglo-Guatemalan Dispute on the Internal Politics of Belize,” Latin American Perspectives 15, no. 2 (1988): 21. ↵

- Mark Moberg, “Structural Adjustment and Rural Development: Inferences from a Belizean Village,” The Journal of Developing Areas 27, no.1 (1992): 4. ↵

- Annita Montoute, “CARICOM’s External Engagements: Prospects and Challenges for Caribbean Regional Integration and Development,” German Marshall Fund of the United States (2015): 2, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep18854. ↵

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), The World Factbook: Ethnic Groups, 2018, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/fields/400.html#PM ↵

- Isabeau J. Belisle Dempsey, “Framing the Center: Belize and Panamá within the Central American Imagined Community,” SUURJ: Seattle University Undergraduate Research Journal 4, no. 13 (2020): 87, https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/suurj/vol4/iss1/13 ↵

- Pete Wilkinson, “Tourism—The Curse of the Nineties? Belize—An Experiment to Integrate Tourism and the Environment,” Community Development Journal 27 (1992): 386. ↵

- Carol Key and Vijayan K. Pillai, “Tourism and Ethnicity in Belize: A Qualitative Study,” International Review of Modern Sociology 33, no. 1 (2007): 133. ↵

- Ibid., 139. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Joseph O. Palacio, The Garifuna: A Nation Across Borders (Benque Viejo del Carmen, Belize: Cubola Productions, 2005), 145. ↵

- Young and Young, “The Impact of the Anglo-Guatemalan Dispute on the Internal Politics of Belize,” 9. ↵

- Young and Young, “The Impact of the Anglo-Guatemalan Dispute on the Internal Politics of Belize,” 11; Josef L. Kunz, “Guatemala vs. Great Britain: In Re Belice,” The American Journal of International Law 40, no. 2 (1946): 385, doi:10.2307/2193198. ↵

- Young and Young, “The Impact of the Anglo-Guatemalan Dispute on the Internal Politics of Belize,” 12. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Tony Thorndike, “The Conundrum of Belize: An Anatomy of a Dispute,” Social and Economic Studies 32, no. 2 (1983): 65. ↵

- Young and Young, “The Impact of the Anglo-Guatemalan Dispute on the Internal Politics of Belize,” 21. ↵

- O. Nigel Bolland, Colonialism and Resistance in Belize: Essays in Historical Sociology (Belize City: Cubola, 1988), 214. ↵

- Anthony J. Payne, “The Belize Triangle: Relations with Britain, Guatemala and the United States,” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 32, no. 1 (199): 124, doi:10.2307/166131 ↵