5 Drafting the Essay

DRAFTING THE ESSAY

What kind of writing is the assignment asking you to do? Is this a review? A summary? An argumentative piece?

Will you need to do research and cite sources? If this is the case, you can probably set aside ideas that will be difficult to do research for, such as a story about a personal experience. These might be better suited to a different assignment.

- Is there a specific length requirement? You will want to look through your ideas to make sure you’re focusing on ones that you will be able to have an in-depth and well-supported conversation about in this amount of space. If the assignment length is short, you won’t have space to clarify a complex relationship between two ideas, and if the assignment is a longer one, you will need a topic that allows for that length of conversation without repeating yourself or focusing on just one support.

- How much time do you have? If the assignment is due soon, you may want to work with a topic you already know something about, rather than try to learn a new-to-you set of ideas from scratch in a hurry.

- Make sure any ideas you are considering focusing on for this work match the goals of the assignment.

Once you have narrowed your ideas to ones that fit the assignment parameters, look for connections between the remaining ideas. Does one support another? Are a few of them different ways of looking at the same thing? Can two combine to make a stronger, more complete topic? Does one spark your interest in a way the others don’t?

If you complete these steps and find you have no topics left that have passed these tests, you will want to generate new ideas, maybe with a different generation method. If you are still looking at several potential topics after this process, pick just one of them, or one tightly-connected group of them, to work with for this project.

You have plucked one idea (or closely related group of ideas) out of all of your possible ideas to focus on. Congratulations! Now what? Well, now you might write about that topic to explore what you want to say about it. Or, you might already have some idea about what point you want to make about it. If you are in the latter position, you may want to develop a working thesis to guide your drafting process.

Writing the Thesis Statement

What is a Working Thesis?

A thesis is the controlling idea of a text. Depending on the type of text you are creating, all of the discussion in that text will serve to develop, explore multiple angles of, and/or support that thesis.

But how can we know, before getting any of the paper written, exactly what thesis the sources we find and the conversations we have will support? Often, we can’t. The closest we can get in these cases is a working thesis, which is a best guess at what the thesis is likely to be based on the information we are working with at this time. The main idea of it may not change, but the specifics are probably going to be tweaked a bit as you complete a draft and do research.

Thesis Statements: Your Main Point

A thesis statement needs a topic and an opinion/claim about that topic:

Topic/Opinion:

- Summer in Guanajuato very educational

- MHCC nursing school quality program

- Michael Phelps best swimmer in history

- Damian Lillard best Blazer in history

- Women in sports broadcasting have come a long way

- A longer school day several benefits

Once you have your topic and opinion, develop a thesis statement.

Examples:

- My summer in Guanajuato was a wonderful educational experience.

- Mt. Hood Community College School of Nursing provides a quality education for its students.

- Michael Phelps is without a doubt the most accomplished swimmer in the history of swimming.

- Damian Lillard is the best basketball player to wear a Trailblazers jersey.

- Women are playing a much more integral role in sports broadcasting.

- A longer school day for the elementary school children has several advantages.

A Strong Thesis Statement:

- Tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- Is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- Directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- Makes a claim that others might dispute.

- Is usually a single sentence at the end of your first paragraph that presents your argument to the reader.

How do I write a Thesis?

Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Then you can start developing your thesis, but you might change it as you go.

Your thesis is the engine of your essay. It is the central point around which you gather, analyze, and present the relevant support and philosophical reasoning which constitutes the body of your essay. It is the center, the focal point. The thesis answers the question, “What is this essay all about?”

A strong thesis does not just state your topic but your perspective or feeling on the topic as well. And it does so in a single, focused sentence. Two tops. It clearly tells the reader what the essay is all about and engages them in your big idea(s) and perspective. Thesis statements often reveal the primary pattern of development of the essay as well, but not always.

An effective thesis statement has several key components:

- States the central idea of the essay in a complete sentence

- Reveals the author’s opinion or attitude about the topic

- Often lists subtopics/ provides a general outline of the essay

- Is usually found atthe end of the introduction

An effective thesis does not…

- Ask the reader a question (i.e. “What is beauty?”}

- State the obvious (i.e “This essay will be about my definition of beauty” or “In this essay I will define beauty.”)

Thesis statements are usually found at the end of the introduction. Seasoned authors may play with this structure, but it is often better to learn the form before deviating from it.

Writing Paragraphs

How to develop and organize paragraphs is a problem that plagues many beginning college writers. How do you start a paragraph? How can you help your reader understand the main idea? How do you know when you’ve included enough details? How do you conclude? You might also wonder when you need to break a paragraph and start a new one or how help your reader transition from one idea to the next.

What is a Paragraph?

Let’s begin by defining this concept of the paragraph. A paragraph is a group of sentences that present, develop, and support a single idea. That’s it. There’s no prescribed length or number of sentences. Paragraphs rarely stand alone, so most often the main topic of the paragraph serves the main concept or purpose of a larger whole; for example, the main idea of a paragraph in an essay should serve to develop and support the thesis of the essay. (For more on thesis statements, see “Finding the Thesis” earlier in this “Drafting” section of this text.)

Similarly, the main idea of a paragraph in a letter serves the overall purpose of the letter, whether that purpose is to thank your Aunt Martha for the thoughtful birthday sweater, or whether the purpose is to inform a local business that you’re dissatisfied with the quality of a product or service that you purchased.

Topic Sentences

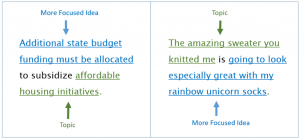

The job of the topic sentence is to control the development and flow of the information contained in the paragraph. The topic sentence takes control of the more general topic of the paragraph and shapes it in the way that you choose to present it to your readers. It provides a way through a topic that is likely much broader than what you could ever cover in a paragraph, or even in an essay. This more focused idea, your topic sentence, helps you determine the parts of the topic that you want to illuminate for your readers—whether that’s a college essay or a thank you letter to your Aunt Martha. The following diagram illustrates how a topic sentence can provide more focus to the general topic at hand.

Think about some places where you might commonly find general topics presented with more focus, perhaps in news stories, textbooks, or speeches. The topic of a news story might be a deadly forest fire that’s burning out of control, while the focus of the topic might be about careless humans. The topic of a chapter from a medical text might be phlebotomy (the practice of drawing blood from a patient), while the focus of a section of that chapter might be about safe disposal of used needles. Maybe the topic of a persuasive speech is organic produce, while the focus of the speech is about the importance of supporting local organic farms.

Most topics are expansive, so they require more focus—whether in a thesis statement or a topic sentence—to provide a narrower view of the broader subject. This narrower and more focused view also often seeks to persuade the reader to see things from the writer’s perspective.

Placement of Topic Sentences

What if I told you that the topic sentence doesn’t necessarily need to be at the beginning? This might be contrary to what you’ve learned in previous English or writing classes, and that’s okay. Certainly, placing topic sentences at or near the beginning of paragraphs is a fine strategy, especially for beginning writers. If you announce a topic clearly and early on in a paragraph, your readers are likely to grasp your idea and to make the connections that you want them to make.

Now that you’re writing for a more sophisticated academic audience though—that is an audience of college-educated readers—you can use more sophisticated organizational strategies to build and reveal ideas in your writing. One way to think about a topic sentence, is that it presents the broadest view of what you want your readers to understand. This is to say that you’re providing a broad statement that either announces or brings into focus the purpose or the meaning for the details of the paragraph. And if you think of the topic sentence as the broadest view, then you can think about how every supporting detail brings a narrower—or more specific—view of the same topic.

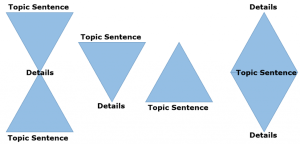

With this in mind, take some time to contemplate the diagrams in the figure below. The widest point of each diagram (the bases of the triangles) represents the topic sentence of the paragraph. As details are presented, the topic becomes narrower and more focused. The topic can precede the details, it can follow them, it can both precede and follow them, or the details can surround the topic. There are surely more alternatives than those that are presented here, but this gives you an idea of some of the possible paragraph structures and possible placements for the topic sentence of a paragraph.

Characteristics of a Good Topic Sentence

If a reader or teacher comments that your paragraph lacks unity, you probably need a better topic sentence (or maybe you don’t have one yet). So, how can you spot a good topic sentence when you’ve written one? A good topic sentence might meet the following criteria:

- Signals the topic and also the more focused ideas of the paragraph

- Presents an idea or ideas that are clear and easy to understand

- Provides unity to the paragraph (so it’s clear how all supporting ideas relate)

- Omits supporting details

- Engages the reader

There’s no right order in the writing process for identifying or writing the topic sentence of a paragraph. Some writers begin drafting a paragraph with a main idea already in mind and then decide how to support it. Others begin writing about details, examples, or quotations from sources that they feel somehow relate to what they want to say, writing for a while before deciding what the main idea is. Most writers rely on a variety of strategies that they have developed through trial and error. So don’t let the lack of a main idea hold you back from getting out what you want to say. Write for a while, and a main idea will surely emerge.

The Paragraph Body: Supporting Your ideas

Whether the drafting of a paragraph begins with a main idea or whether that idea surfaces in the revision process, once you have that main idea, you’ll want to make sure that the idea has enough support. The job of the paragraph body is to develop and support the topic. Here’s one way that you might think about it:

- Topic sentence: what is the main claim of your paragraph; what is the most important idea that you want your readers to take away from this paragraph?

- Support in the form of evidence: how can you prove that your claim or idea is true (or important, or noteworthy, or relevant)?

- Support in the form of analysis or evaluation: what discussion can you provide that helps your readers see the connection between the evidence and your claim?

- Transition: how can you help your readers move from the idea you’re currently discussing to the next idea presented? (For more specific discussion about transitions, see the following section on “Developing Relationships between Ideas”).

For more on methods of development that can help you to develop and organize your ideas within paragraphs, see “Patterns of Organization and Methods of Development” later in this section of this text.

Types of support might include:

- Reasons.

- Facts.

- Statistics.

- Quotations.

- Examples.

Now that we have a good idea what it means to develop support for the main ideas of your paragraphs, let’s talk about how to make sure that those supporting details are solid and convincing.

Good vs. Weak Support

What questions will your readers have? What will they need to know? What makes for good supporting details? Why might readers consider some evidence to be weak?

If you’re already developing paragraphs, it’s likely that you already have a plan for your essay, at least at the most basic level. You know what your topic is, you might have a working thesis, and you probably have at least a couple of supporting ideas in mind that will further develop and support your thesis.

So imagine you’re developing a paragraph on one of these supporting ideas and you need to make sure that the support that you develop for this idea is solid. Considering some of the points about understanding and appealing to your audience can also be helpful in determining what your readers will consider good support and what they’ll consider to be weak. Here are some tips on what to strive for and what to avoid when it comes to supporting details.

| Good support

|

Weak Support

|

| · Is relevant and focused (sticks to the point).

· Is well developed. · Provides sufficient detail.Is vivid and descriptive. · Is well organized. · Is coherent and consistent. · Highlights key terms and ideas.

|

· Lacks a clear connection to the point that it’s meant to support.

· Lacks development. · Lacks detail or gives too much detail. · Is vague and imprecise. · Lacks organization. · Seems disjointed (ideas don’t clearly relate to each other). · Lacks emphasis of key terms and ideas. |

Breaking, Combining, or Beginning New Paragraphs

Like sentence length, paragraph length varies. There is no single ideal length for “the perfect paragraph.” There are some general guidelines, however. Some writing handbooks or resources suggest that a paragraph should be at least three or four sentences; others suggest that 100 to 200 words is a good target to shoot for. In academic writing, paragraphs tend to be longer, while in less formal or less complex writing, such as in a newspaper, paragraphs tend to be much shorter. Two-thirds to three-fourths of a page is usually a good target length for paragraphs at your current level of college writing. If your readers can’t see a paragraph break on the page, they might wonder if the paragraph is ever going to end or they might lose interest.

The most important thing to keep in mind here is that the amount of space needed to develop one idea will likely be different than the amount of space needed to develop another. So when is a paragraph complete? The answer is, when it’s fully developed. The guidelines above for providing good support should help.

Some signals that it’s time to end a paragraph and start a new one include that

- You’re ready to begin developing a new idea.

- You want to emphasize a point by setting it apart.

- You’re getting ready to continue discussing the same idea but in a different way (e.g. shifting from comparison to contrast).

- You notice that your current paragraph is getting too long (more than three-fourths of a page or so), and you think your writers will need a visual break.

Some signals that you may want to combine paragraphs include that

- You notice that some of your paragraphs appear to be short and choppy.

- You have multiple paragraphs on the same topic.

- You have undeveloped material that needs to be united under a clear topic.

Finally, paragraph number is a lot like paragraph length. You may have been asked in the past to write a five-paragraph essay. There’s nothing inherently wrong with a five-paragraph essay, but just like sentence length and paragraph length, the number of paragraphs in an essay depends upon what’s needed to get the job done. There’s really no way to know that until you start writing. So try not to worry too much about the proper length and number of things. Just start writing and see where the essay and the paragraphs take you. There will be plenty of time to sort out the organization in the revision process. You’re not trying to fit pegs into holes here. You’re letting your ideas unfold. Give yourself—and them—the space to let that happen.

Developing Relationships between Ideas

So you have a main idea, and you have supporting ideas, but how can you be sure that your readers will understand the relationships between them? How are the ideas tied to each other? One way to emphasize these relationships is through the use of clear transitions between ideas. Like every other part of your essay, transitions have a job to do. They form logical connections between the ideas presented in an essay or paragraph, and they give readers clues that reveal how you want them to think about (process, organize, or use) the topics presented.

Why are Transitions Important?

Transitions signal the order of ideas, highlight relationships, unify concepts, and let readers know what’s coming next or remind them about what’s already been covered. When instructors or peers comment that your writing is choppy, abrupt, or needs to “flow better,” those are some signals that you might need to work on building some better transitions into your writing. If a reader comments that she’s not sure how something relates to your thesis or main idea, a transition is probably the right tool for the job.

When Is the Right Time to Build in Transitions?

There’s no right answer to this question. Sometimes transitions occur spontaneously, but just as often (or maybe even more often) good transitions are developed in revision. While drafting, we often write what we think, sometimes without much reflection about how the ideas fit together or relate to one another. If your thought process jumps around a lot (and that’s okay), it’s more likely that you will need to pay careful attention to reorganization and to providing solid transitions as you revise.

When you’re working on building transitions into an essay, consider the essay’s overall organization. Consider using reverse outlining and other organizational strategies presented in this text to identify key ideas in your essay and to get a clearer look at how the ideas can be best organized. See the “Reverse Outlining” section in the “Revision” portion of this text, for a great strategy to help you assess what’s going on in your essay and to help you see what topics and organization are developing. This can help you determine where transitions are needed.

Let’s take some time to consider the importance of transitions at the sentence level and transitions between paragraphs.

Sentence-Level Transitions

Transitions between sentences often use “connecting words” to emphasize relationships between one sentence and another. A friend and coworker suggests the “something old something new” approach, meaning that the idea behind a transition is to introduce something new while connecting it to something old from an earlier point in the essay or paragraph. Here are some examples of ways that writers use connecting words (highlighted with red text and italicized) to show connections between ideas in adjacent sentences:

To Show Similarity

When I was growing up, my mother taught me to say “please” and “thank you” as one small way that I could show appreciation and respect for others. In the same way, I have tried to impress the importance of manners on my own children.

Other connecting words that show similarity include also, similarly, and likewise.

To Show Contrast

Some scientists take the existence of black holes for granted; however, in 2014, a physicist at the University of North Carolina claimed to have mathematically proven that they do not exist.

Other connecting words that show contrast include in spite of, on the other hand, in contrast, and yet.

To Exemplify

The cost of college tuition is higher than ever, so students are becoming increasingly motivated to keep costs as low as possible. For example, a rising number of students are signing up to spend their first two years at a less costly community college before transferring to a more expensive four-year school to finish their degrees.

Other connecting words that show example include for instance, specifically, and to illustrate.

To Show Cause and Effect

Where previously painters had to grind and mix their own dry pigments with linseed oil inside their studios, in the 1840s, new innovations in pigments allowed paints to be premixed in tubes. Consequently, this new technology facilitated the practice of painting outdoors and was a crucial tool for impressionist painters, such as Monet, Cezanne, Renoir, and Cassatt.

Other connecting words that show cause and effect include therefore, so, and thus.

To Show Additional Support

When choosing a good trail bike, experts recommend 120–140 millimeters of suspension travel; that’s the amount that the frame or fork is able to flex or compress. Additionally, they recommend a 67–69 degree head-tube angle, as a steeper head-tube angle allows for faster turning and climbing.

Other connecting words that show additional support include also, besides, equally important, and in addition.

Transitions between Paragraphs

It’s important to consider how to emphasize the relationships not just between sentences but also between paragraphs in your essay. Here are a few strategies to help you show your readers how the main ideas of your paragraphs relate to each other and also to your thesis.

Use Signposts

Signposts are words or phrases that indicate where you are in the process of organizing an idea; for example, signposts might indicate that you are introducing a new concept, that you are summarizing an idea, or that you are concluding your thoughts. Some of the most common signposts include words and phrases like first, then, next, finally, in sum, and in conclusion. Be careful not to overuse these types of transitions in your writing. Your readers will quickly find them tiring or too obvious. Instead, think of more creative ways to let your readers know where they are situated within the ideas presented in your essay. You might say, “The first problem with this practice is…” Or you might say, “The next thing to consider is…” Or you might say, “Some final thoughts about this topic are….”

Use Forward-Looking Sentences at the End of Paragraphs

Sometimes, as you conclude a paragraph, you might want to give your readers a hint about what’s coming next. For example, imagine that you’re writing an essay about the benefits of trees to the environment and you’ve just wrapped up a paragraph about how trees absorb pollutants and provide oxygen. You might conclude with a forward-looking sentence like this: “Trees benefits to local air quality are important, but surely they have more to offer our communities than clean air.” This might conclude a paragraph (or series of paragraphs) and then prepare your readers for additional paragraphs to come that cover the topics of trees’ shade value and ability to slow water evaporation on hot summer days. This transitional strategy can be tricky to employ smoothly. Make sure that the conclusion of your paragraph doesn’t sound like you’re leaving your readers hanging with the introduction of a completely new or unrelated topic.

Use Backward-Looking Sentences at the Beginning of Paragraphs

Rather than concluding a paragraph by looking forward, you might instead begin a paragraph by looking back. Continuing with the example above of an essay about the value of trees, let’s think about how we might begin a new paragraph or section by first taking a moment to look back. Maybe you just concluded a paragraph on the topic of trees’ ability to decrease soil erosion and you’re getting ready to talk about how they provide habitats for urban wildlife. Beginning the opening of a new paragraph or section of the essay with a backward-looking transition might look something like this: “While their benefits to soil and water conservation are great, the value that trees provide to our urban wildlife also cannot be overlooked.”

Evaluate Transitions for Predictability or Conspicuousness

Finally, the most important thing about transitions is that you don’t want them to become repetitive or too obvious. Reading your draft aloud is a great revision strategy for so many reasons, and revising your essay for transitions is no exception to this rule. If you read your essay aloud, you’re likely to hear the areas that sound choppy or abrupt. This can help you make note of areas where transitions need to be added. Repetition is another problem that can be easier to spot if you read your essay aloud. If you notice yourself using the same transitions over and over again, take time to find some alternatives. And if the transitions frequently stand out as you read aloud, you may want to see if you can find some subtler strategies.

Writing Exercise: try out new transition strategies

Writing Exercise: try out new transition strategies

Choose an essay or piece of writing, either that you’re currently working on, or that you’ve written in the past. Identify your major topics or main ideas. Then, using this chapter, develop at least three examples of sentence-level transitions and at least two examples of paragraph-level transitions. Share and discuss with your classmates in small groups, and choose one example of each type from your group to share with the whole class. If you like the results, you might use them to revise your writing. If not, try some other strategies.

Writing Introductions

“You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression.” This common axiom reminds us just how much weight people place on their first experiences, whether it be with a person, a road trip, or a piece of writing. Catching readers’ attention may be the most important work you do when you write, because if you lose them in the introduction, you don’t get a chance to share your message with them later.

What is the Purpose of an Introduction?

Introductions have two jobs:

- Catch readers’ attention.

- Introduce the focus and purpose of your writing.

How do I accomplish these jobs without giving away all of my essay in the introduction? I mean, how do I know what will hook readers’ attention without sharing all the cool details?

Great questions! You might start by using this simple formula and then choosing a method from the list below.

Formula

A good introduction = new information + ideas that everyone may not agree with. To put it another way, if your piece begins with an idea most people know and agree with, it’s less likely to pull readers in. People are made curious by new ideas and opinions that have multiple perspectives or may be controversial.

Methods

The following are some methods and examples for introducing a topic and getting your reader’s attention.

Method: Share an interesting, shocking, or little known fact or statistic about your topic. Starting your paper with a fact or statistic that gives your readers insight into your topic right away will peak their curiosity and make them want to know more. It will also help you establish a strong ethos, or credibility, from the very beginning.

Example: According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 68% of prison inmates do not have a high school diploma.

Method: Tell an anecdote or story that will help readers connect with your topic on a personal level. Sharing a human interest story right away will help readers connect with your topic on a personal level and will help to illustrate way your topic matters.

Example: Today, Jimmy Santiago Baca is a well known American poet, but when he was twenty he entered prison illiterate and had to teach himself to read over the five years he spent behind bars.

Method: Ask a question that gets readers curious about the answer. People tend to want to answer questions when they’re presented with them. This provides you with an easy way to catch readers’ attention because they’ll keep reading to discover the answer to any questions you pose in the introduction. Just be sure to answer them at some point in your writing.

Example: Can prisons rehabilitate prisoners so they’re able to return to their communities, find jobs, and contribute in positive ways?

Writing Exercise: Good or Bad Introduction?

Writing Exercise: Good or Bad Introduction?

One way to improve your introduction-writing skills is to look at different choices that other writers make when introducing a topic and to consider what catches your interest as a reader and what doesn’t. Read the introductions below about teenagers and decision making. Which ones pull you in? Which ones are less interesting? What’s the difference? Work with peers to decide.

- Throughout history, teenagers have challenged the authority of adults. They do this because they want to be given more freedom and to be treated like adults themselves. This can cause real problems between teens and the adults in their lives.

- Some days my sixteen-year-old niece, Rachael, does all of her homework, helps friends study after school, and practices her cello, and other days she forgets her books at school, lies about where she’s going, and doesn’t do her chores. This sporadic behavior seems like it comes out of nowhere, but it turns out teenage brains are different from adult brains, causing teens to sometimes not think about consequences before they act.

- If teenage brains aren’t fully formed, causing them to act before they think about the risks they’re taking, should teens be restricted from some adult freedoms like driving, working, and socializing without adult supervision?

- Teenagers are known to be less responsible than adults, so they should have at least some adult guidance to make sure they stay safe. Without adult supervision, teens will make poor decisions that could put them at unnecessary risk.

- According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the frontal cortex in the brain, where reasoning and thinking before acting occurs, is not fully formed in teenagers. However, the amygdala, “responsible for immediate reactions including fear and aggressive behavior,” is fully formed early in life. This means teens aren’t as good at considering the consequences of their behavior before they react, so the adults in their lives should limit the risks in their lives until they’re better able to reason through them.

Writing Exercise: Write an Introduction

Writing Exercise: Write an Introduction

Now that you’ve had an opportunity to think about some different approaches and techniques for writing introductions, let’s practice. Find an entry in your journal or a draft of a piece of writing you’re working on this term and use what you’ve learned in this section to write an attention-grabbing introduction to your piece.

If you don’t currently have a piece to work with, you can write an introduction using one of the following scenarios. Read through the following list and choose one. One to three sentences is enough.

- Persuade your local school board members that the elementary school should change the way it teaches sex education.

- Persuade teens to travel to a foreign country before they graduate from college.

- Give some tips to new parents that will help lower their stress and make their new baby feel safe and loved.

- Inform young athletes who may want to play football of the possible risks and benefits.

- Review a movie, book, product, or trip for someone thinking of making one of these purchases to help them decide that they should or shouldn’t do it.

Share your introduction with your classmates and discuss what about it is effective and how it could be improved.

Writing Conclusion

Studies have shown that the human brain is more likely to remember items at the beginnings and ends of lists, presentations, and other texts. When people recall the last thing they read or hear, that’s called the “recency effect” because they’re remembering the most recent information they’ve encountered (“Recency Effect”). This is why the last thing you write is so important. It’s your final chance to make an impression on your readers.

What is the Purpose of a Conclusion?

Conclusions have two jobs:

- Leave readers with something to think about.

- Clarify why your topic matters to them and the larger community (whether that be the class, their neighborhood or the whole wide world).

Sometimes the conclusion is called the “So what?” section of the text because it helps readers understand the significance of your subject.

What Techniques Keep Readers Thinking about the Topic at the End of a Piece of Writing?

Funny enough, some of the same methods that work for the introduction also work for the conclusion. However, the formula is a little different.

Formula

A good conclusion = a call to action and/or a connection between the topic and the reader. In other words, because you’re trying to end your piece, you don’t want to start making new claims or sharing new research. Instead, you’ll want to help readers see how they relate to your subject matter. Sometimes this means suggesting that the reader do something specific. That’s a call to action. You can also end by raising questions related to your topic or by making suggestions for how this topic may develop in the future. Leaving readers with interesting ideas to think about is key to a successful conclusion.

Methods

The following are some methods and examples for concluding an essay and giving your readers a sense of closure or an idea of what you would like them to think about or do next.

Method: Make a call to action. The goal of a call to action is to prompt readers to do something.

Example: Citizens who agree that music education should be a part of all public schools in the United States can make a difference by writing their representatives, going to a school board meeting, and when a ballot initiative comes around, voting to fund music education.

Method: Ask a rhetorical question. A rhetorical question is meant to make people think, but not necessarily come to an answer. Often, the answer to rhetorical questions is clear right away, but the deeper significance needs to be pondered.

Example: Should schools in the U.S. be concerned with the kind of emotional and cognitive development that music education prompts? If we’re interested in educating the whole child, not just the most academic parts of the brain, then the answer is yes, and we have to reconsider our priorities when it comes to school funding.

Method: Share an anecdote or story that will keep the issue in the forefront of the readers’ minds. An interesting snapshot of someone’s life or story about an intriguing character will help humanize the topic and help the readers remember your message. If you used an anecdote or story in the introduction, this is an opportunity to reconnect with that at the end of your piece.

Example: Lin-Manuel Miranda, the creator of the hit Broadway musical Hamilton, says that arts education saved his life. He went to an elementary school where the sixth grade put on a famous play every year—everything from Fiddler on the Roofto The Wizard of Oz—but by the time Miranda’s class was in sixth grade, the teachers had run out of plays appropriate for children, so they had the sixth graders write their own musicals in addition to performing all the musicals from the previous years. That four-hour-long musical extravaganza was Miranda’s first experience of writing and acting in his own production (Raskauskas). The opportunity that his teachers provided him turned into a lifelong passion. All students should have that same opportunity to connect with the arts in meaningful ways.

Method: Share a quote by an expert or historical figure. Choose a quote from someone who is well known in a relevant field and who has expertise on your topic. This will lend your conclusion credibility and leave readers with something powerful to consider.

Example: As Oliver Sacks notes in his book Musicophilia, “Rhythm and its entrainment of movement (and often emotion), its power to ‘move’ people, in both senses of the word, may well have had a crucial cultural and economic function in human evolution, bringing people together, producing a sense of collectivity and community” (268). Our schools aim to foster that same sense of community, which is why music must be part of a well rounded education.

Writing Exercise: Good or Bad Conclusion?

One way to improve your conclusion-writing skills is to look at different choices that other writers make when concluding a topic and to consider what feels satisfying or thought-provoking to you as a reader and what doesn’t. Read the conclusions below about teenagers and decision making. Which ones pull you in? Which ones are less interesting? What’s the difference? Work with peers to decide.

- Should teens be given complete freedom? Probably not, but a measured level of responsibility helps kids of all ages learn to trust themselves to make good decisions. This is especially important for teens since they will be adults very soon.

- Parents who want to teach their teenagers to be responsible decision makers can start by talking to their teens regularly about the kinds of decisions their teens are being faced with and allowing teens to make decisions about anything that won’t put them in immediate danger. This may be difficult at first, but the reward will come when parents see their teens feeling more confident in the face of difficult decisions and more ready to face the adult world.

- As stated above, research shows that the teenage brain isn’t fully matured, so adults should consider this when deciding how much freedom to give them.

- According to the AACAP, teens are more likely to make decisions based on emotions without thinking first. This means they’re more likely to “engage in dangerous or risky behavior.” Therefore, teens need to be protected until they’re old enough to make thoughtful decisions.

- Now that Rachael has been given the freedom to make some big decisions in her life, she’s more willing to talk to her parents when she needs advice or isn’t sure about something. Even though she sometimes makes mistakes, her parents trust that she will learn important lessons from those mistakes, and they help her feel supported when she experiences a failure. Raising a teenager isn’t easy, but this family has found a method that’s working for this particular teen.

Writing Exercise: Write a Conclusion

Writing Exercise: Write a Conclusion

Now that you’ve had an opportunity to think about some different approaches and techniques for writing conclusions, let’s practice. Find an entry in your journal or a draft of a piece of writing you’re working on this term and use what you’ve learned in this section to write a compelling conclusion to your piece.

If you don’t currently have a piece to work with, you can write a conclusion using one of the scenarios below. Read through the following list and choose one. Then, practice writing a concluding statement or paragraph on the topic. One to three sentences is enough.

- Persuade your local school board members that the elementary school should change the way it teaches sex education.

- Persuade teens to travel to a foreign country before they graduate from college.

- Give some tips to new parents that will help lower their stress and make their new baby feel safe and loved.

- Inform young athletes who may want to play football of the possible risks and benefits.

- Review a movie, book, product, or trip for someone thinking of making one of these purchases to help them decide that they should or shouldn’t do it.

Share your conclusion with your classmates and discuss what about it is effective and how it could be improved.

(adapted from Academic Writing I by Lisa Ford)