7.1 Identifying Sources

Finding sources of information is not difficult; however, finding and identifying reliable, relevant sources that address specific research questions can be challenging.

Assuming that by the time you visit the library or search the internet to gather information, you have identified a topic, something general that you want to explore, or formulated a question based on an issue that concerns you and that others need to know about. You may even have a working thesis that identifies a gap between what you think and believe and what others have written; identifies a misperception about an issue that you wish to correct; builds on ideas that others have written about; or tests a hypothesis against claims that different writers have made. Your topic, question, or working thesis will determine the nature and extent of information you need, and your search will help you refine your topic, issue, and question.

Consult experts who can guide your research

Before you embark on a systematic hunt for sources, you may want to consult with experts who can help guide your research. The following experts are nearer to hand and more approachable than you may think.

Your writing instructor. Your first and best expert is likely to be your writing instructor, who can help you define the limits of your research and the kinds of sources that would prove most helpful. Your writing instructor can probably advise you on whether your topic is too broad or too narrow, help you identify your issue, and perhaps even point you to specific reference works or readings you should consult. Your instructor can also help you figure out whether you should concentrate mainly on popular or scholarly sources.

Librarians at your campus or local library. In all likelihood, there is no better repository of research material than your campus or local library, and no better guide to those resources than the librarians who work there. Their job is to help you find what you need. Librarians can give you a map or tour of the library and provide you with booklets or other written guides that instruct you in the specific resources available and their uses. They can explain the catalog system and reference system. And, time allowing, most librarians are willing to give you personal help in finding and using specific sources, from books and journals to indexes and databases.

Expert in other fields. Perhaps the idea for your paper originated outside your writing course, in response to a reading assigned in, say, your psychology or economics course. If so, you may want to discuss your topic or issue with the instructor in that course, who can probably point you to other readings or journals you should consult. If your topic originated outside the classroom, you can still seek out an expert in the appropriate field.

Research manuals, handbooks, and dedicated websites. These resources exist in abundance, for general research as well as for discipline-specific research. They are especially helpful in identifying a wide range of authoritative search tools and resources, although they also offer practical advice on how to use and cite them. your writing instructor or a librarian probably point you to one of these manuals or handbooks or recommend a website that is best suited to your research.

Develop a working knowledge of standard sources

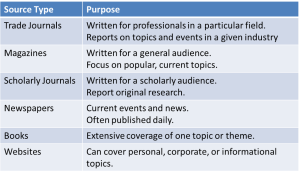

As you start searching for sources, it helps to know broadly what kinds of sources are available and what they can help you accomplish. Table 5.1.1 below lists a number of types and purposes of sources you often rely on when looking for materials.

Distinguish between primary and secondary sources

As you define the research task before you, you will need to understand the difference between primary and secondary sources and figure out which you will need to answer your questions. Your instructor may specify a preference, but chances are you will have to make the decision yourself. A primary source is a firsthand, or eyewitness, account, the kind of account you find in letter, newspapers, or research reports based on original research, including statistics, interviews, with individuals, or focus groups. A secondary source is an article, book, newspaper, or any other source that does not constitute a report based on firsthand information. For example, it can be a summary of data and conclusions in research reported in a journal article or an event that the writer did not experience firsthand.

Distinguish between popular and scholarly sources

To determine the type of information to use, you also need to decide whether you should look for popular scholarly books and articles. Popular sources of information – newspapers like USA Today and The Chronicle of Higher Education, and large-circulation magazines like Time Magazine and Field & Stream, — are written for general audience. This is not to say that popular sources cannot be specialized: The Chronicle of Higher Education is read mostly by academics, Field & Stream by people who love the outdoors. But they are written so that any educated reader can understand them.

Scholarly sources, by contrast, are written for experts in a particular field. The New England Journal of Medicine may be read by people who are not physicians. But they are not the journal’s primary audience. In a manner of speaking, these readers are eavesdropping on the journal’s conversation of ideas; they are not expected to contribute to it. The articles in scholarly journals undergo peer review. That is, they do not get published until they have been carefully evaluated by the author’s peers, other experts in the academic conversation being conducted in the journal. Reviews may comment at length ab out an article’s level of research and writing, and an author may have to revise an article several times before it sees print. And if the reviewers cannot reach a consensus that the research makes an important contribution to the academic conversation, the article will not be published.

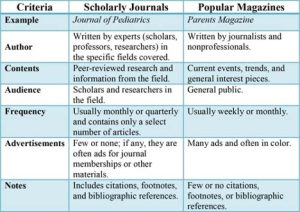

When you begin your research, you may find that popular sources provide helpful information about a topic or an issue. Later, however, you will want to use scholarly sources to advance your argument. You can see from Table 5.1.2 that popular magazines and scholarly journals can be distinguished by a number of characteristics.

Table 5.1.2 Popular Magazines versus Scholarly Journals

Again, as you define your task for yourself, it is important to consider why you would use one source or another. Do you want facts? Opinions? News reports? Research studies? Analyses? Personal reflections? The extent to which the information can help you make your argument will serve as your basis for determining whether a source of information is of value.

Steps to Identifying Sources

- Consult experts who can guide your research. Talk to people who can help you formulate issues and questions.

- Develop a working knowledge of standard sources. Identify the different kinds of information that different types of sources provide.

- Distinguish between primary and secondary sources. Decide what type of information can best help you answer your research question.

- Distinguish between popular and scholarly sources. Determine what kind of information will persuade your readers.

Media Attributions

- 5.1.1 Types of Sources

- 5.1.2 Popular Magazines versus Scholarly Journals