1.4 Rhetorical Appeals

Once we understand the rhetorical situation out of which a text is created, we can look at how those contextual elements shape the author’s creation of the text. That is, the classical appeals (or proofs), which are ways to classify authors’ intellectual, moral, and emotional approaches to getting the audience to have the reaction that the author hopes for. These appeals allow writers to communicate more or less persuasively with the audience.

Rhetorical appeals include ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos. These are classical Greek terms, dating back to Aristotle, who is traditionally seen as the father of rhetoric. To be rhetorically effective (and thus persuasive), an author must engage the audience in a variety of compelling ways, which involves carefully choosing how to craft his or her argument so that the outcome, audience agreement with the argument or point, is achieved.

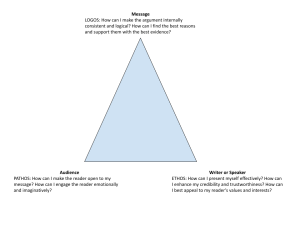

As explained in the previous section, the Rhetorical Situation can be visualized as triangulating relating three main elements: Writer, Subject (or Message), and Audience. Three of the Rhetorical Appeals (logos, pathos, and ethos) can be mapped onto that triangle in the following way:

Logos, pathos, and ethos can be represented as distinct corners of a triangle, but it’s important to emphasize the sameness and interconnectedness of that triangle. Just as the message, audience, and writer all contribute to the final product, the rhetorical appeals are mutually reinforcing and intertwined.

The following video explains these three rhetorical appeals in a concise way.

Media Attributions

- 1.4 Rhetorical Appeals and the Rhetorical Situation